Visual Argument

|

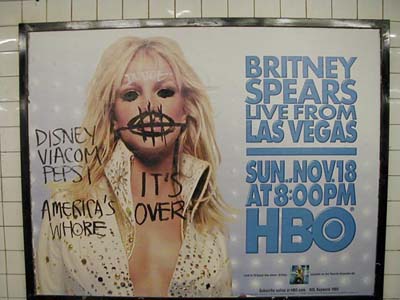

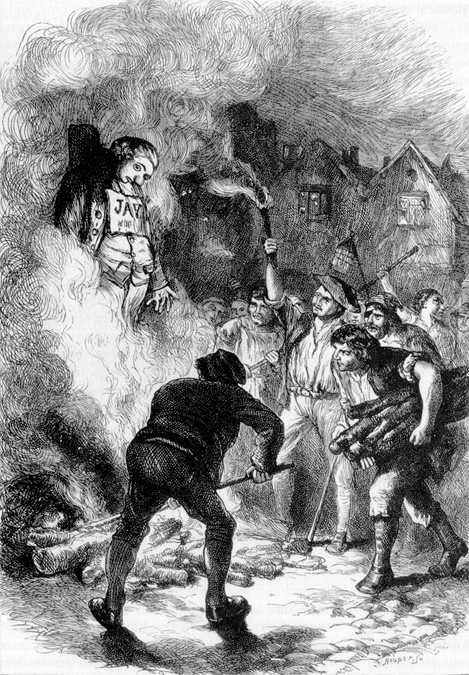

In J. Anthony Blair’s (2004) formulation, a single image can make a visual statement, while a visual argument emerges when that image is placed in a wider context. For the purposes of this webtext, I read Blair with the understanding that a visual argument requires, at a minimum, two images in proximity to each other. The argument of this webtext emerges in the "space between" the images, not unlike the way the viewer of a comic "fills in" the conceptual space between two panels, what Scott McCloud (1993) termed "closure in the gutter" (p. 60-93). An important move in any comparative history is to identify structural similarities between the seemingly disparate. Each image in this composition depicts a specific historical event. When viewed in isolation, each depicts events separated in time and space, as well as by their proximate causes and specific historical circumstances. But in juxtaposing these images, I wish to draw attention to their underlying structural similarities. That is, the macro-argument of this composition. The micro-argument emerges in the mind of each viewer, who is invited to map these similar structures onto each other. The viewer creates an argument by apprehending the common patterns that emerge from their viewing of the juxtaposed images. The macro-argument advanced here is that the events captured in each image cohere together and should be viewed as part of a larger whole; I make the claim that these events are not disparate but are homologous. (Note that I am not claiming a causal connection between these events, but rather an associative connection.) Luddism and iconoclasm—or rather, the impulse that fuels both actions—are structurally homologous acts. Luddism is usually understood as an attack on technology, but I think it better to understand that specific act of vandalism as an attack not on the device but as an attack on what that device represents. Similarly, I wish to view iconoclasm not as an attack on specific religious imagery but on what that imagery represents. That impulse makes Luddism and iconoclasm—and all the other acts of principled vandalism depicted here—more alike than we might think. The viewer creates a micro-argument by viewing these juxtaposed images within the boundaries established by the macro-argument. Look at the first three sets of images: a church burning in Birmingham, Alabama; a defaced poster of Britney Spears; United Auto Workers smashing a Japanese import. Looking at the first image alone is to situate it in its own particular historical context: a specific time, place, setting, set of causal forces, etc. Similarly, the defaced poster is the result of historical conditions in another time and place. By placing one image next to the other, the viewer is invited to reflect on the commonalities in these two acts of violence against objects. What does the Church symbolize? What does the image of Britney Spears symbolize? What are the commonalities of these two acts of vandalism/Luddism/iconoclasm? Can we perceive a common pattern between these two historically different acts? Importantly, how does your understanding of the meaning of the first image change as a result of its juxtaposition next to the Spears poster? Does it change again when a new juxtaposition emerges? Now, add the third image: How does this event influence your understanding of the meaning of the other two images? Then, of course, after a few seconds, new images and new juxtapositions emerge, each adding layer upon layer of meaning. Throughout the swirl of juxtapositions, what common themes and patterns emerge that connect these acts of violence against objects? Answering these questions creates the micro-argument of this composition, the viewers’ particular mapping of these homologous acts. Where there is one macro-argument, there are as many potential micro-arguments as there are viewers of this composition. Juxtaposed images create a meaning that is established extralinguistically, before language. Visual arguments work at the level of perception, not logic; visual arguments have an ineffable quality formed outside of language. Therefore, because it works extralinguistically, unfolding in the eye of each viewer, the visual argument for this webtext is as much the responsibility of the viewer as it is the designer. I concede much of the interpretation to the viewer while retaining my role as procedural author, as Janet Murray (1997) claimed in relation to electronic media:

Each iteration of the images establishes new narrative and rhetorical possibilities. Within the set of visual choices I have established as the procedural author, a viewer can exercise agency by making associative connections between the images. Those associative connections are as important a component of the visual argument as are my choices as procedural author. |

|

|

||

|

||