DIGITAL SCHOLARSHIP

The digital component of the writing for our course reflected the most powerful rhetorical force of the presidential campaign, which wasn't a particular person or line of argument, but the collective force of the internet, especially in the form of fake news, but also memes, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media. This focus was reflected in some of the readings chosen for the syllabus, such as the Humans of New York interview circulated through Facebook and added to the syllabus by Brie Cronin and the Between Two Ferns interview with Clinton (Funny or Die, 2016) added by Dana Krugle, and in some of the projects developed in the course, which were enabled by the course's open pedagogical approach.

Social Media

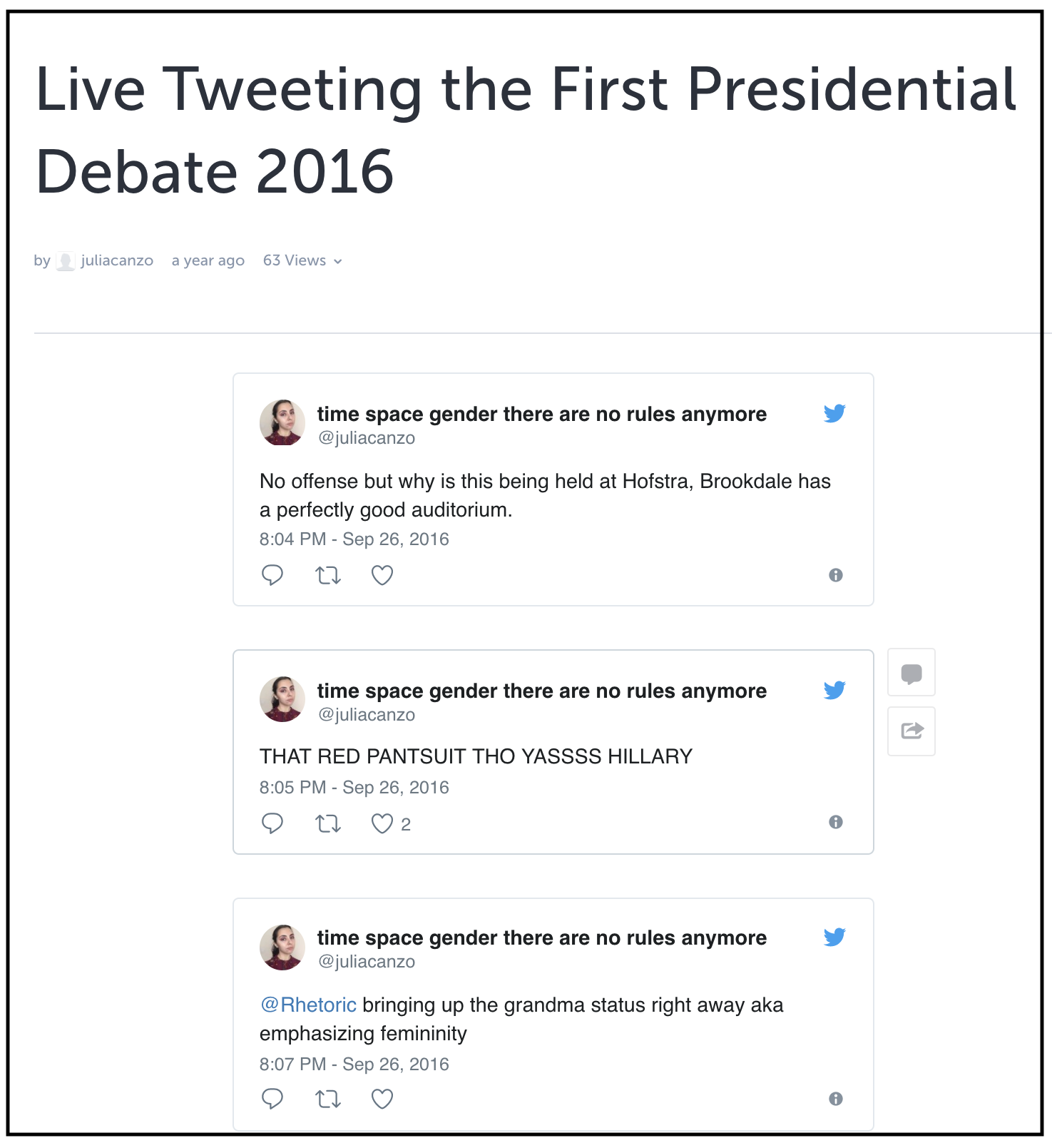

Julia Canzoneri chose to live tweet each of the three presidential debates for her class project. She then analyzed how live tweeting was a form of political analysis that bridged academic analysis and social media. Beneath what she characterizes as "all-capitalized, grammatically nightmarish cheers for Clinton and denouncement of [her opponent]," she raised important questions about the candidates' rhetorical strategies, while also filling some tweets with humor and silliness. Canzoneri analyzed how the combination of social media and academic analysis allowed an emphasis on emotional responses in both genres. The rhetorical analysis also took on a new format when she analyzed how her thoughts were retweeted. The retweets demonstrated the power of sharing and crowdsourcing analysis.

by juliacanzo a year ago 63 views

time space gender there are no rules anymore [Canzoneri's Twitter handle]

@juliacanzo

No offense but why is this being held at Hofstra, Brookdale has a perfectly good auditorium.

8:04 PM - Sep 26, 2016

time space gender there are no rules anymore

@juliacanzo

THAT RED PANSUIT THO YASSSS HILLARY

8:05 PM - Sep 26, 2016

time space gender there are no rules anymore

@juliacanzo

@Rhetoric bringing up the grandma status right away aka emphasizing feminity

8:07 PM - Sep 26, 2016

Transcript of Canzoneri's tweets in image above.

Canzoneri's project found that the kind of analysis being provided by social media users is reaching wider audiences, providing these audiences the opportunity to switch their roles and become rhetors through sharing and commenting. This has changed political rhetoric, as shown through the candidates' differing strategies. The longer, more thoughtful responses of Clinton couldn't fit into a sound bite and be retweeted or shared as easily as her opponent's statements.

As Alex Kreichman concluded in his exploration assignment analyzing the relationship between satire, political rhetoric, and what he called the conflation of entertainment and politics, what also came about was the role of snark in the election, so much so that he characterized the debates as similar to an internet flame war. The tags of the readings we added to the syllabus helped Kreichman to synthesize the posts analyzing humor and satire in the election. The synthesis assignment then led to his overall observations about the role of snark in election rhetoric

Memes

What were once considered silly memes or immature/trollish comments are now examined as legitimate commentary on candidates' positions. The memes circulating tapped into these emotions and arguments.

Cronin made her class project creating the Hillary Hate Dank Meme Stash. On Facebook, though not exclusive to Facebook, there are "meme stashes," places where users upload memes they find or make or to comment on memes. Concentrating on memes created by Bernie Sanders supporters, she asked the question, how do Sanders supporters use meme creation to make Clinton appear less relatable, less trustworthy, and less fit?

Analyzing the effect of memes on the 2012 election, Ben Wetherbee (2015) observed that the influence of "the binders full of women" meme on the outcome of that election indicates that scholarship on rhetoric needs to examine how "Topoi often function as memes that evolve to suit rhetorical circumstances," and perhaps how memes function as topoi. He wrote, "Individual rhetors will struggle especially to deliberately coin successful Internet memes. As in 'binders,' the most successful Internet memes typically work against the intentions of the meme's original 'author' because the culture of memetics online favors the humorous, ironic, parodic, and pop-culturally literate over the deliberately, purposefully polemical."

The 2016 version of the binders full of women meme that illustrated Wetherbee's point was the #ImANastyWoman hashtag which became a tag on our site. We examined how the women of social media reclaimed and flipped the phrase "Nasty Woman" through a series of funny tweets, shirts that said "Nasty Woman" 2016, and the resurgence of Janet Jackson's "Nasty Video." However, while, turning the insult into an ironically feminist battle cry may have helped some people to better understand the lack of respect for women of Clinton's opponent, finding humor in the phrase may have also softened its offensive nature. In other words, the use of humor may have dampened the sense of outrage and detracted from the feminist cause by trivializing the gravity of the situation. As Kreichman's project noted, humor and irony are used on social media, television, and T-shirts to subvert containment rhetoric and deconstruct patriarchy, as well as show how satire is intrinsically kairotic in that it responds to current issues and seizes the opportunities presented by the present; in these ways, satire holds on the potential to mobilize—but also creates the mere illusion of doing something when in reality we are doing nothing and are complicit in the status quo. Our discussions of the memes included the readings and projects of the course called attention to how we critiqued the rhetoric of the memes as we participated in this rhetoric.

Other memes included putting Clinton's face on iconic or pop culture images, such as Reddit users that put Hillary's face on the Mother of Dragons from Game of Thrones, a way of claiming images to suit a narrative.

Krugle's exploration assignment analyzed this practice and used similar tactics in putting Clinton's face on iconic heroes to portray her as a heroine in the story of the election.

In fact, in Krugle's synthesis/lit review post, she decided to put together a video using the images we included in different posts on our site. She used the images to tell the story not only of the election but of the conversation on the election on our site.

Images and Imaging

This claiming and distribution of images illustrated the matter of the construction of Clinton's image and her power or lack of power over shaping that image. One requirement for each post, whether a reading or literature review or exploration assignment, was to include images and other media. This presented a challenge for some of us who had only written traditional papers, but as the semester continued—and thanks to Krugle's innovative approach—we began to see the story of the election in the images we used for our posts and the importance of images in that story.

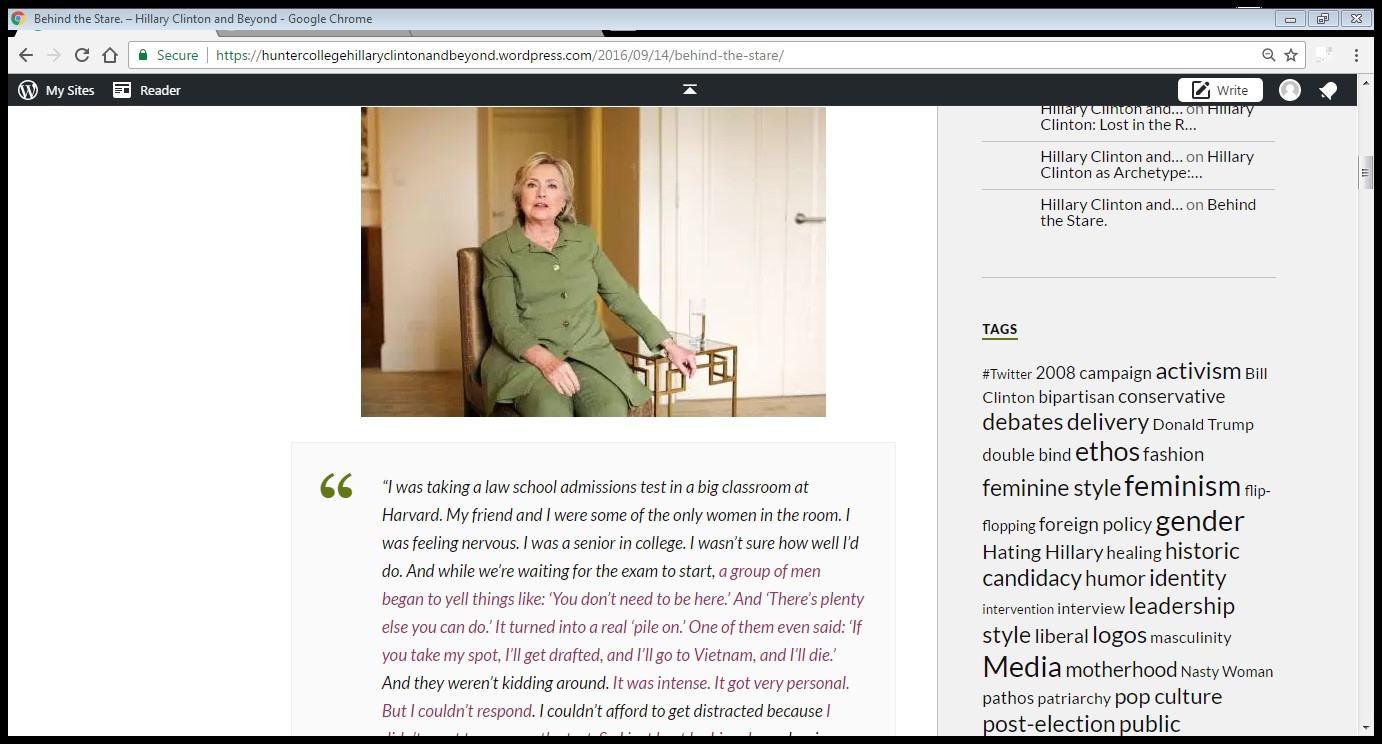

One story our syllabus then documented was how Clinton continually fought to reclaim her image. The Humans of New York interview circulated on Facebook and added to our syllabus by Cronin was Clinton telling the story of experiencing sexism when she went to take the law school exams, which she then cited as a reason for her perceived aloofness.

Though some may interpret this strategy as Clinton desperately trying to soften the abrasive persona people associate with her, the post allowed Clinton to tell her own personal story of facing overtly sexist ridicule, which made some students in our class like her for the first time. Communicating through this particular venue reached more of the people who needed to see Clinton as "relatable."

Melissa Harden's work in the course analyzed the two Hillary's that emerged in this story of imaging: savior and villain. Harden chose as a reading a Frontline PBS (2016) video on how Clinton had to makeover her image and change her last name after Bill Clinton lost the election for governor of Arkansas to show how femininity or perceived lack of femininity affected the relatability narrative created by the media. Harden related the point made in this video to Clinton's Humans of New York interview and guest spots on Between Two Ferns (Funnie or Die, 2016) and Broad City (Comedy Central, 2016) were efforts to use social media to bolster her ethos and reclaim her image.

Sarah Parente's project chose to address the issue of image through exploring Clinton's logical appeals to voters' values by digitally annotating Clinton's speeches. Using the medium of the Hypothes.is free digital annotation software to comment on the speech made the rhetorical analysis physically or virtually closer to the actual text of the speech as opposed to writing a paper about the speech and quoting from it. It also allowed for multiple people to add annotations, such as in the annotation of Clinton's (1995) Beijing speech.

Digital Scholarship Takeaways

Thus, could we see Parente's digital annotations, like Canzoneri's tweets, Cronin's meme stash, Krugle's memes, and the many videos and social media materials we aded to the syllabus as a way of becoming part of the narrative of the election? Just as Kreichman's synthesis chose to create a literature review from students' comments on the readings on the syllabus rather than the readings themselves, Parente often quoted the work of her peers in her digital annotations, making all of us a part of that narrative as well. Thus, instead of only analyzing social media and its role in the election, or even using social media to house coursework, the digital components of the course brought the tenets of social media to an academic context.

Next: RHETORICAL APPEAL