with

performance photographs of

with

performance photographs of

By Marianne Goldberg

Be To Want I (1996-present) is a work for dance and text that lives simultaneously in three incarnations. The first is in live performances that have been staged from New York City to Oregon. The second is in an invented genre that I call a "performance piece for print"--a poetic assemblage of dance, language and images, published in journals. The third is an emerging venture designed for reading in a computerized environment, a "performance piece for hypertext." In this essay I will explore relationships between these three forms of the work and introduce an excerpt from Be To Want I, Hypertext. The complete version of this hypertext will be published by the DIAL Magazine later this year.

with

performance photographs of

with

performance photographs of

Christianne Brown

FROM STAGE TO PAGE

In 1986, as a choreographer and writer, I first began to imagine "performance pieces for the printed page" as a way to bring together dance and language. I designed text and choreographed movements to be photographed specifically for the two-dimensional format of the printed page. Envisioning the printed journal as a miniature stage, the reader could hold the text in hand and activate it by turning its pages. This new, unwieldy form strained the mechanics of reproduction. With each flight of fantasy, my overlays, juxtapositions and attempts at opacities fast outgrew print production techniques available in the eighties. I sensed that increasingly complex images would best be developed in an electronic medium, but at that time, even in New York City, image and text layout was still done by hand in most publications. Yet in concept, the ways I began to work with print processes could, in retrospect, be considered as hypertextual.

The impetus for creating a hybrid form such as the performance piece for print stemmed from a strong desire to forge a place where dance work could be linked to conceptual thought, including cultural theory. Contemporary forms of dancing were, for the most part, isolated within wonderfully bare studios with huge white walls and expansive wood floors that became home to me as I studied there for parts of each day. Mostly in SoHo, these dance studios were connected with choreographers who had participated in the highly innovative Judson Church performances of the sixties and postmodern works of the seventies and eighties. Occasionally words were uttered as part of their choreography, but not the kind of theoretical language I heard just up the street, in debates I engaged in as part of a separate world, at New York University. I longed to bring together these different ways of knowing the body and language, whether through juxtaposition or even sheer collision, if necessary. As I crisscrossed Manhattan, I found no place where these twin loves of mine occupied the same room.

I began to turn upside down every commonplace I had been taught about epistemology--by considering dancing a theoretical act and writing a visceral one. One late night in my home study, with photos of dancing and cut-outs of words sprawled out on the floor all around me, I determined to reconceive the printed page as a stage. The page would become an open cultural space where the body could dance amidst languages of all kinds--theoretical, poetic, metaphoric, antimetaphoric, and euphoric. My colleagues, a collective of editors at Women & Performance journal, read my first efforts and encouraged me to go further and further with this genre. A whole new world opened up. The first fruit of my explorations was Ballerinas and Ball Passing, published in issue six of the journal in 1988.

I felt at home immediately in this new space for writing and dancing, where I could live out my imagination differently than on stage, yet as passionately. In this form, word and body became co-equals. When I partnered them I found I could participate in a fuller sense of human perceptual experiences than I had ever known. I fantasized that I actually "lived" inside those journal pages, in a utopian realm where radically different ways of knowing could coexist and shed light on one another. This new sphere, where dance and word could come together, led me to reconceive my live performances as well. I strove to develop a facility to switch back and forth between extremely kinesthetic ways of performing and quite intellectual and theoretical inquiries. Transforming the usual podium lecture into a theatrical form, I took poetic license with an audience's ability to follow cross-references between body and word. I made puns that crossed over from language to gesture. Through images, metaphors, or pure instinctual leaps of imagination, these performances affirmed that kinesthetic and intellectual forms of intelligence could be intertwined.

Onstage I began to include technological images of physical

gestures and words. I utilized video and photo stills, typeset text on

placards, and text in motion typed live onto large computer monitors. These

shifts in media address, from one mode of communication to another, gave

me the notion that I might find a new place to inhabit as a performer,

in the cracks between media. Again, in retrospect, this concept of multiplicity

was similar to hypertextual reading. It was not until over a decade later

that I formally delved into hypertext by taking Robert Kendall's on-line

course through The New School. There I found another place where forays

into multi-genre work can be shared with a diverse community. I have not

yet encountered other hypertextualists who work specifically with the body

and language, yet projections of human thought into multiple dimensions

of word, image, video, and sound form a parallel to my crossover modes.

FROM PAGE TO HYPERTEXT

I began to envision "performance pieces for hypertext," in which I could project gesture and movement onto the computer screen via the internet, as I had previously onto the printed page. In a world still so subdivided into disciplines such as literature, choreography, visual art, videography, and so on, hypertext offers a space in which an artist is actually encouraged to overlap various genres. In dance (as in other arts), the modernist separation of the senses has brought great beauty in purity of movement, as distinct from theater, language or music. By focusing on one strand of human perception, the art of human movement, its essence as a separate entity has been explored. Yet being asked by educational institutions to choose between body or mind, movement or language, as a medium for a lifework, cuts off access to the ecstasy of crossing aesthetic borders. Hypertext and hypermedia embrace this act of crossing modes as a new art form in itself.

Hypertextual composition calls upon reading or viewing as an act of linkage, bridging gaps--gaps in time, space, or modes of thought. Previously unbridgeable forms can be joined in complex ways. Different parts of the brain begin to work in concert, linking diverse aspects of human imagination. Whether in microseconds or minutes, there is a time of suspension between images, as the viewer waits for them to be realized onscreen. During this suspension, parts of images become visible before the whole. Similarly, as readers scroll down they first see the top of an image appearing and then later its lower edge disappearing upward. Even though they may not be considered finished images in themselves, chance pauses in the forward motion of the scroll reveal them. Often the momentarily "incomplete" images are quite beautiful and arresting. In live screen time, the instants between fully completed images are small-scale gaps in time, revealing intricately detailed perceptions. Momentary gaps also happen as the reader clicks on links and waits to connect to new destinations. Larger-scale gaps may exist between entire genres that come to share the same screen or to link to one another, whether coincidentally or purposely.

MULTI-GENRE LITERACY

Multiplicity is familiar to those coming to hypertext from the perspective of nonlinear live performance. Yet hypertext offers an interplay with contemporary performance that goes far beyond this initial similarity. Both forms present readers/viewers with textual crossroads that fork into multiple paths, rather than follow more obvious, linear paths. Other major commonalities between these two forms include author-viewer collaboration and overlays of image, text, motion, or sound. Perhaps one of the most intriguing parallels between hypertext and nonlinear performance is the opportunity they both offer for readers to develop a new kind of literacy that is not limited to the linguistic. The screen can become an open space where imaginary projections of human perceptions can play out, if viewers recognize the multiple genres and can read between the lines. It is ironic that within such a technological environment aspects of human inner life and subjective awareness can be articulated so well.

Hypertextual linkage is the crux of this process of heightened perception, since intuitive choices of both author and reader are made obvious in this act. Through linkage, literacy can come to involve "reading" a textual "sentence" that begins as a grouping of words, runs head on into an image, then swerves around a gesture, and completes with a video or sound clip. Actively taking part in creating sequences by choosing links, viewers explore the multiple meanings of textual passages, alongside the author. Linkage brings closer together differing modes of knowing--whether visual, linguistic, or kinetic--and even whole epistemological patterns that historically have developed within separate spheres. Aesthetic epiphanies that happen within single-genre perception can also occur within hypertexts, but they differ. Insights in hypertext often stem from the layering of genres. With depth and subtlety in imagery and linkage structures, kinds of awareness grow that are distinct to this new medium.

Whether the joining together of separate modes of experience becomes integrative or jarring depends in part on how images are linked or overlaid. Either experience can be full of discovery. Even if at first somewhat disorienting, hypertext can offer a challenging creative space if the reader perserveres and lets go of usual approaches to "reading." Authors and viewers alike suspend "knowing," resisting the comfortable closure of more familiar ways of understanding. Once "inside" the process of the piece, the reader, like the author, begins to grapple with this new reading experience. In facing a partially designed screen and trying out different routes of traversing it, readers may actually create associative links that go beyond what the writer conceived. Writers can encourage this kind of daring by posing links that offer choices that intentionally intercept usual habits of literacy. Reading left to right, right to left, up to down, hieroglyphically or phonetically--these are human accomplishments based in thousands of years of linguistic evolution. Yet there are also other ways to read still to be invented. For instance, many of us do not learn how to consciously "read" kinesthetic imagery to the same depth or detail as we do the word. Yet these forms can be deeply moving and resonant, whether in themselves or combined with words, if readers begin to trust their own basic human responses to them.

From that trust, greater multi-genre literacy can develop, simply through active reading. For those who feel themselves in uncertain territory, aesthetic terror or boredom can often be eased by considering the text as a form of visual-kinetic poetry. This frees the viewer from having to "solve" a text's literal meaning and allows a sensual, associative approach. Once increasingly comfortable in this place of not-knowing, readers may find they understand much more than they originally thought possible as to how to receive the flow of images in a fertile way. When meaning-making is intentionally open, both writer and reader can let go of the urgency to understand where a text is heading in a literal way and become more open to intuitive response.

Be To Want I, HYPERTEXT

Taking Be To Want I as

an example, I focus the hypertext around a network of questions. Rather

than answer those questions with closure, I hope that the images might

be turned round and round in the reader's mind. This process of attentiveness

and intuition allows inklings of understanding to grow. For both live and

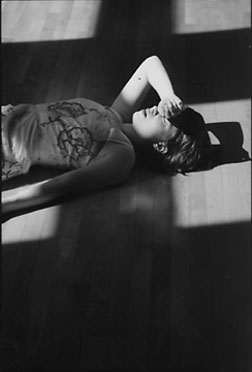

print versions of Be To Want I, I collaborated with Christianne

Brown, who performs in the visuals both in this essay and in the hypertext

excerpt. We worked together through improvisation to consider questions

about "femininity." I chose the seemingly simple subject of childhood memories

of tutus as a way into this exploration. Verbal text combined with physical

exploration led to movements one would not think possible while wearing

a tutu, quite different than those of classical ballet. When performed

in a traditional silver and pink fantasy of netting and glittering stone,

these unconventional moves, along with explorative spoken text, lead to

a sense that, with tongue in cheek, femininity is being taken apart. In

its focus on gender issues, Be To Want I is a sequel to Ballerinas

and Ball Passing. So it is fitting that it will again be published

as a performance piece for print byWomen & Performance journal.

In contrast to the limited graphics capabilities of the late eighties, we now are able to compose the printed piece with Quark Express and Photoshop. This allows direct work with overlays and juxtapositions of body and word. I hope to create a link between the performance piece for print and the new hypertextual version so that readers can move back and forth between print and screen worlds (in addition to the experience of the live stage performances when those are accessible to them). The hypertext excerpt of Be To Want I included here is in many ways a deconstruction of its printed precursor. Rather than simply transfer the printed version to the Web, I took apart the overlays that we had constructed with Quark, returned to their initial component parts, and started over again.

This approach, actually the result of technological problems, turned out to lead to a fresh start, bringing into focus a specifically hypertextual way of recreating the piece. Although direct transfer from Quark to the Web proved impossible with the software available to us at the time, I would still like to include high-resolution overlays from the print version in the hypertext. Perhaps we will be able to achieve this with one of the new technologies capable of transposing complex graphics to the Web, such as Go Live. Just as when transposing a work from stage to page, I began to consider hypertext an entirely new medium. To find out how this new form might contribute to the continuing exploration of cultural and personal questions we conceived initially in our live improvisations, we will allow the hypertext to transform the piece once again. As we further develop the hypertext-in-progress, I plan to set up the technology right in the dance studio. With the images up onscreen, Christianne can interact with them from a kinesthetic point of view. As director for these sessions, I envision the screen as an electronic stage and we will play with its theatricality.

The excerpt of Be To Want I included here offers links (outlined in pink) as beginning points to try out an initial experience in multi-genre literacy. The entire piece is still in process. It will be published online by The New School through the DIAL Magazine that will open late this fall. Christianne Brown will rejoin me to develop other layers for the hypertext, including video and sound clips of her dancing and speaking. At The New School, Lisa White has been helpful in solving some of the more complex technical aspects of the piece. She has offered to collaborate with us, bringing her expertise in the creation of high-quality video excerpts to our dance clips for the Web. This will allow us to re-connect the hypertext version to its sources in movement and vocal improvisation.

VIEWER INTERACTIVITY

One aspect of interactivity in hypertext is that viewers can choose where to enter the piece and in what order to proceed. In Be To Want I choices may be by visual, kinetic, or linguistic initiative. Through linkages readers can make personal sequences that lead them to identifications (or dis-identifications) with the cultural icon of the ballerina. In rummaging through their own related autobiographical histories as they click on links, personal memories may guide their movement through the text, directly effecting what happens on screen. As inspired by the icons, and specifically by the e-mail link, viewers are invited to recall or reinvent their own memories of childhood tutus and language games. In this process the "I" of Be To Want I comes to live somewhere between performer, director, and reader. Autobiography is shared and performed. In contributing text and more generally by making intuitive decisions as to how to create their own order of events, the reader becomes a protagonist in this adult storybook.

As another aspect of the interactive potential of hypertext, I would like viewers to be able to move text and images around, constructing and deconstructing the overlays. I also want to make visible their re-visions to other readers. So far we have not found a way to realize these ideas technically. I hope to find hypertext programmers who would be interested in collaborating on such a project. For inspiration in developing this vision, I will call on situations I have set up previously in live performances, such as times when I have given videocameras to viewers and projected their spontaneous images onto monitors during the dance. With the help of Robert Kendall, I was able to design an e-mail link so that readers can send back their own memories in words, and hopefully also in images. Readers can e-mail text to us and attach files with photos, video clips, or other visual materials. I, for instance, keep on my wall a drawing of a trio of ballet dancers that I created at age seven. This would be just the kind of material for readers to send back. As authors we may transform these texts into the inverted language structures of "dollspeak" and then transport them back into the public piece to be available to other readers. When you respond via the e-mail form, please let us know if we are free to include or alter your responses. If you also send us your e-mail address or phone number, we may contact you to discuss details.

As we embark on this new creative path of adding reader text to the piece, we will continue to ask questions about what hypertextual forms bring to cultural and autobiographical issues in Be To Want I. Revelations come with new mediums. In connecting new words, visuals, movement, or sound, the imagery of this piece will expand, as will the capacity in range of multi-genre literacy of its viewers. As e-mail images and text that come to us are woven back into the website on a regular basis, this hypertextual interactivity brings a different form of communication to the work. Here it allows the notion of a collectively created autobiography, seemingly a contradiction in terms, yet possible through the shared inner visions of many individuals. The piece sits between author and viewer and information travels in both directions, rather than, as traditionally, from author to viewer only. (In yet another parallel between hypertext and performances of the eighties and nineties, reader response theory has contributed to a similarly altered semiotic model of communication onstage.) In the excerpt of Be To Want I included here, we hope you will take the opportunity to respond on the form provided. When you come to the link that takes you from "bikers" to "theater," as you click again on the enlarged image of the theater, you will find yourself at an intensely pink page. Continue to follow two more links and you will arrive at an e-mail form with a space for you to input your memories and attach files with your response to the question, "What is your first memory of a tutu?"

INTERACTIVITY AND REHEARSAL PROCESS

In rehearsals I began by asking the same question of Christianne as we are now asking of readers: "What is your first memory of a tutu?" The image of a tutu in a young girl's mind is often one of great fantasy and perplexity. Our creative work followed this process of question and response, a compositional mode I call "performative interviewing." This mode allows performer and director to let their imaginations come into synchrony in more and more expansive ways. Just as readers can be invited to be "co-writers" of certain parts of text, so can performers be included in the creative process during workshops when we develop material for the piece. As director I aim for a close connection with the performer's improvisational momentum by continuing to ask questions that evoke physical and verbal immersion in the imagery. Christianne responds with gestures and words and has also contributed structural and editorial insight.

During future rehearsals, we will call on these

previous experiences of synchrony from our improvisations to achieve an

integration of electronic equipment--keyboards, computer monitors and video

cameras--into our creative process in the dance studio. I have already

brought this equipment into live performances many times. Now we will work

to evolve a direct interaction of the performer with the actual creation

of screen images in Quark or Photoshop as part of the rehearsal

process. We will bring images up onscreen during improvisations and design

them in tandem with onsite recordings of live dancing and speaking. With

these sound and video clips, we will develop a more complex linkage structure

for the hypertext.

LIVE BODY AND TECHNOLOGY

In bringing performer and technical equipment together, I hope the new linkage structures we create will reflect a balance of physical and technological inspiration. Too often the performer's body is considered an "object" for the camera, then for the scanner, and eventually for viewers. In my work the person who is dancing contributes insights that effect compositional choice. As both a dancer and a choreographer, I have had the opportunity to direct or collaborate in such experimentation. Sometimes it is actually the performer who can best decide on camera position or lighting subtleties for a certain sequence, because of a strong physical connection with the subject matter. I have seen how much creativity begins to flow when technology and the body are equal partners in a project.

My dream is to form an ongoing collaborative team for

the creation of hypertextual performance pieces for the Web. Just as choreographers

need collaborators with expertise in lighting design, costume, or sound

when creating for live performance, we need persons knowledgeable in complex

aspects of hypertextual technology when we compose for the screen environment.

When choreographer, performer, and graphics experts improvise together,

live, on the spot, unexpected and often powerful images emerge. The physically

inspired creative forces of the live performer can bring to the process

a sense of immediacy, with unique ideas for overlays, opacities, and choices

of sequence. Anyone who might be interested in working with us in this

way is encouraged to contact us through my e-mail address: bodytext@aol.com.

DOLLSPEAK

To give readers a sense of how workshop process with live performers can lead to new imagery and structural ideas, I would like to describe how Be To Want I evolved. Our original improvisations with images from childhood memories of tutus led to the discovery of a childlike language game we have come to call "dollspeak." During rehearsals Christianne remembered that she had kept a tiny pink plastic ballerina doll in her childhood dresser drawer--not to save the doll as a treasure, but because she did not quite know what else to do with the ballerina. In rehearsals I asked if she could speak from the point of view of the plastic doll, who lived mostly in darkness, exposed to cracks of light only when the drawer was opened. The ballerina began to "speak" through Christianne in an internal monologue of word and gesture. Through spontaneous language games, we began to transform this text into a dialect of retrograde. This backwards language parallels the act of an adult woman who remembers by moving back in time in her mind. Christianne's sensations as a child are filtered through the lens of her adult memory. They are reconstructions of the past, but from the point of view of the present. As does the process of recreating memory, the retrograde structure of the dollspeak dialect takes apart language and thought patterns and puts them back together in a rearranged form. With these surprising linguistic shifts, notions of identity and femininity begin to open up.

The overall hypertext structure parallels the inversion of the dollspeak grammar. The entire piece moves forward and backward. The beginning icon on the entry page (as conventionally approached in the upper left hand corner) is linked to the last icon (in the lower right corner). That last icon is linked back to the first, suggesting a pendulum-like oscillation of time. These links are the only two to repeat the same image--one of Christianne in a moment of active imagination. The opening photo is in correct proportion, while the last is distorted, as if through a mirror in time. In the more extensive version that will be published by The New School online gallery, it will be possible to navigate the expanded hypertext in an endless loop of inversions. The usual linearity of moving "backward to the past" or "forward to the future" can be reversed, as new ideas about time are explored: perhaps it is also possible to move forward to the past or backward (in memory) in order to create a new future.

As the reader winds through these layers of time, past and future are revealed as co-existing in complex ways within each individual, from childhood to adulthood. In childhood Christianne did not want to be like the identical manufactured toy that serves as an icon of femininity to millions of girls across America when they open their jewelry boxes and see the tiny ballerina magically spinning in place. Yet after in-depth exploration in rehearsal, a kind of truce was formed. From the point of view of an adult re-imagining the past, Christianne began to find a rapport with the doll. As the dollspeak text unfolds, the little ballerina evolves into more of a comrade-in-arms, a co-conspirator in an escape plan from a life of stasis. Instead of looking to the doll as a cultural model of femininity, Christianne begins to find a desire in common with her: with the force of existential necessity, they each aspire to understand themselves differently. Perhaps the doll longs, as has Christianne, to run across native Montana sapphired fields, to exist vitally in dreams of a wilder movement life.

DOORWAYS

Together child, adult woman, and doll carve out a space of communication and imagination through memory, hope, dreams for the future, and re-creation of the past. In their shared backwards language, they help each other find a way through a disintegrating landfill of cultural imagery. In rehearsals the theme of a doorway began to recur in Christianne's improvisational gestures. Recalling particular doors in her childhood home as they swung open and closed, other memories came forward, appearing and disappearing in her mind. On a recent trip back home to Montana, she took photos of the actual doorways from the perspective of a child's height, intentionally crouching down to assume a posture of looking upward. In the context of the piece, the doorways begin to serve as metaphors for apertures of the imagination. Viewers will be able to enter into the Be To Want I, Hypertext through any of fourteen miniature pink outlines, in doorway (or sometimes window) shapes. Some contain images of actual doorways, and others, by extension, doorways of the mind--entry points into new dimensions of time and space. The stage, traditionally considered a mirror of realism, here might be reconsidered as a doorway.

IDENTITY SHIFTS AND HYPERMEDIA

Through the process of hypertextual reading, it may be possible to form a different identity--or, to identify differently with such all-pervasive icons as the tutued ballerina. As the two-dimensional lit screen takes on a magical sheen, it transforms into a personal theater, its margins like theatrical wings. Readers can catapult themselves inside the margins and into the hypertextual space by acts of imagination, as they might onto a stage during live performance. For Christianne and eventually for the doll, an inversion of that act of entering the hypertextural theatrical space takes place. The doll hopes to catapult herself out of her synthetic pink skin into a place of greater choice and potential identity, somewhere beyond the confined frame of the screen. She imagines she will end up in a landfill as part of the trash of childhood, thrown out by the young girl. Yet then she will at least be out--with a hope of moving on, rather than disintegrating, perhaps picked up by a scavenger to end up in some antique store. Or perhaps she can initiate some tranformation of identity herself, once out of the idolized position of cultural model of femininity.

Hypertexts are particularly malleable to readings with potential for epiphanies in identity transformations. Screen play offers opportunities to try on newly shared identities and throw them out if they do not fit. The trash icon is always available on the desktop. Viewers can make these try-out choices anonymously, with Web identities concealed by fake or theatrical names. Perhaps a "community" might even be found--a support group for discarded ballerina dolls--via the internet. Others anywhere in the world might share similar dreams. Conversations can be fantastical amongst Web cohorts. Unknown to one another beyond their messages, they take on characters, wearing masks like participants in Renaissance ballets at their masqued balls. Of course viewers can also choose to state their actual names and identities and connect with us or other readers directly via their e-mail links. What is culled from these forays can be a whole new persona, who develops a different way of making sense--or put another way, a means of stopping making sense according to well-worn semiotic pathways. If carefully crafted, these shifts in awareness could give hypertextual forms the potential to become profoundly transformative for both personal and cultural identity. In the gaps between linkages, a kind of fertile daydreaming can open up, ultimately changing ways readers "think" when traversing a page, screen, or stage.

To offer an example of cross-media reading and its potential for shifts in identity, I refer the reader to the screen titled, "faces," from Be To Want I. At first glance one encounters a series of identical squares filled with abstract forms that, if viewed in close up, reveal a part of Christianne's face, honing in on her left eye. Three rows of identical eyes extend across the screen. In between each row are lines of text composed only of the letter "I"--one line of "I's" in pink, the other in white. As readers' eyes move from white to pink, passing over the screen images of "eyes," an intimation of a conversation about identity arises between reader, the child, and the doll. (Throughout the text the doll "speaks" in pink letters and Christianne in white.) The plays of meaning between "eye" and "I" suggest complex questions about identity formation, about what it means to speak as "I." As an additional layer of imagery, this conversation sits atop a wallpaper-like background of tiny ballerina dolls. Upraised arms frame their heads in the well-known "fifth position" gesture from ballet training. In miniature, the shape of two arms framing a head could be construed as a little eyeball.

The eyes, the "I's" and the little eyeball dolls together

offer insights into the construction of identity. When readers find the

first part of a hypertextual "sentence" as an image, the next as a word,

and the next a gesture--the sequence forms a new kind of cross-genre "grammar."

Gathered together within a single sphere of experience, on one electronic

page, these different genres come together as "hypermedia," offering possibilities

for making meaning differently. (Here I use the term "hypermedia" as a

genre that is an extension of hypertext, with a greater emphasis on images

and diverse media.) This exploration of identity, of how the pronoun "I"

might be articulated within the hypermedia form, is echoed in the print

version of Be To Want I. The printed piece is published in a particular

issue of Women & Performance journal devoted to themes of autobiography.

In both the printed and hypertext versions of Be To Want I, the

mystery of autobiography and identity unfolds in an expanding multiplicity

of visual-gestural-linguistic poetry. Yet if a viewer can not yet conceive

of "reading" across media in this way, all these connections will remain

invisible. Just as a person who has not learned to recognize letters as

parts of words which then become parts of sentences is considered "illiterate"

in that common form of reading, those unfamiliar with the codes of hypermedia

may not know how to "read" it.

How do those new to the form begin to look for hypertextual resonances? A simple invitation to trust basic sensual experience is a good beginning. Even the slightest flickers of insight might lead readers to risk following their intuition. Then connections between linguistic, kinesthetic and visual forms begin to cohere. Hypermedia is not anywhere nearly as accessible as popular media images in advertising or on MTV but those more known forms may help a reader begin to feel familiar with nonsequitur linkages and image overlays in hypermedia. Unfortunately visual training based on ads might actually lead viewers to stop short of more subtle interconnections available in the hypermedia form. Sequences in TV advertising often display extremely quick cuts that do not give much time for conscious thought. Yet juxtapositions in ads can give back complex information if pondered more fully--particularly about how an ad can pull on a reader's propensity to purchase products for metaphoric as well as practical reasons. Viewers may relate to ad imagery in powerfully subliminal ways that contribute to identity formation in our culture.

Readers coming from popular forms will hopefully find that hypertext and hypermedia hold great potential. As part of traditions based in centuries of permutations of literary forms, historical references, and narrative structures, hypertexts descend from the novel, the poem, or non-fiction treatise, even as they break out into new territory. Some hypertextual linkages may intentionally pull readers out of narrative thinking and bring them instead into a present time engagement with textual imagery. Focusing on an intense passage in an associative way can bring non-linear insight, through happenstance or synchronicity, rather than through direct causal reasoning. Even a buildup and then obliteration of accumulating imagery offers alternative ways of making sense, or nonsense, probing the edges of human imagination.

Be To Want I readers will likely initially interpret textual transitions according to previous reading habits, either from books or from other multimedia forms. But as a new kind of specifically hypertextual structure begins to come together in different ways for each reader, resonances expand. Nuances of rhythm, texture, plays with spatial form, or other perceptual experiences may entrance a reader's imagination. Through choices of links, a reader might, for instance, focus on the image of a person with arms spinning and then abruptly shift to a close up of her face--not for any linear reason, but through choosing a link inspired spontaneously by their own curiosity. The link between a spin and a face traverses a gap, offering a kind of perception that actually happens all around us at every moment of every day, often in mysterious overlays and sequences, if only we notice them. Whether through image continuity or discontinuity, through intentional association or chance, multi-layered input comes to us every split second of our "ordinary" lives. In the "virtual" life of hypertext, some linkages may recall previous events, or foreshadow others that will be encountered at a later time, again depending on how the reader chooses to move through the text.

Connotations gather in a reader's mind. As associative structures begin to form, links are important instances of transition that manifest choice. Links are like forks in the road. The text will not move forward (or backwards) without the active choice of hypertext readers. Through their textual choices, an increasingly complex network of meanings accrue. This is how readers become co-authors. Interrelationships between images, texts and gestures arise and intermingle in new ways in each reader's mind. Everything linked can become related--when gaps are bridged in a spirit of active and open exploration.

ENDNOTES:

1. How to locate a copy of the print version of Be To Want I in the "Autobiography" issue of Women & Performance journal (Volume 10, #2, Issue 19). Please write to Women & Perfomance, c/o Department of Performance Studies, New York University, Tisch School of the Arts, 721 Broadway, New York, NY 10003. The website of the journal is: http://www.echonyc.com/~women.

2. To respond or to debate issues in this essay,

please send your comments to: bodytext@aol.com.

3. For photography credits, please refer to credits

in the introduction of the excerpt of Be To Want

I .

4. To view the complete hypertext at DIAL, please go to the following address:

http://www.dialnsa.edu/i_galler/magazine.