Listening Roundtable for Sleepwalking 2: A Mixtap/e/ssay

February 21, 2019 | Minor Hall | University of Virginia

Moderated by Njelle Hamilton

Featuring Lanice Avery, A.D. Carson, Marcus "Truth" Fitzgerald, Jack Hamilton, Deborah McDowell, and Guthrie Ramsey

Sleepwalking 2 album cover

The listening roundtable is presented below in full, in the order it took place. It's organized for listening like a mixtape playlist with an intro and outro I have written and recorded to frame the discussions. The headings in the webtext menu indicate the speaker leading the comments through that portion of the conversation. The written content below is primarily a transcription of the audio features in this webtext.

Prologue

"Yes, yes."

February 21, 2019, The Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia hosted a listening roundtable for Sleepwalking 2 [a mixtap/e/ssay | OTR]. The roundtable was moderated by Njelle Hamilton, associate professor in the Department of English and Carter G. Woodson Institute for African and African-American Studies at the University of Virginia. The featured participants were Lanice Avery, assistant professor of women, gender, and sexuality and psychology at the University of Virginia; Marcus "Truth" Fitzgerald, Chicago-based producer and rapper; Jack Hamilton, associate professor of media studies and American studies at the University of Virginia; Deborah McDowell, director of The Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies and Alice Griffin Professor of English at the University of Virginia; and Guthrie Ramsey, Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Music at the University of Pennsylvania.

The roundtable was co-sponsored by the Woodson Center and the Department of Music at UVA and was the result of conversations between me and Dr. McDowell concerning my work and ways it might be made legible to my academic peers and colleagues as I attempt to navigate my career on the tenure track. It would be smart for me to think about what kinds of work counts toward tenure as I continue recording and releasing music as a primary facet of my academic contribution. One of our considerations was that rap music as an academic form might require different forums for engagement to invite and encourage academic audiences to participate in conversations about and around the work. This consideration was less about legibility than it was about the conditions for engagement that focused on the work—the words, the sounds, the samples, the production, the collaborative process, etc.—and the form.

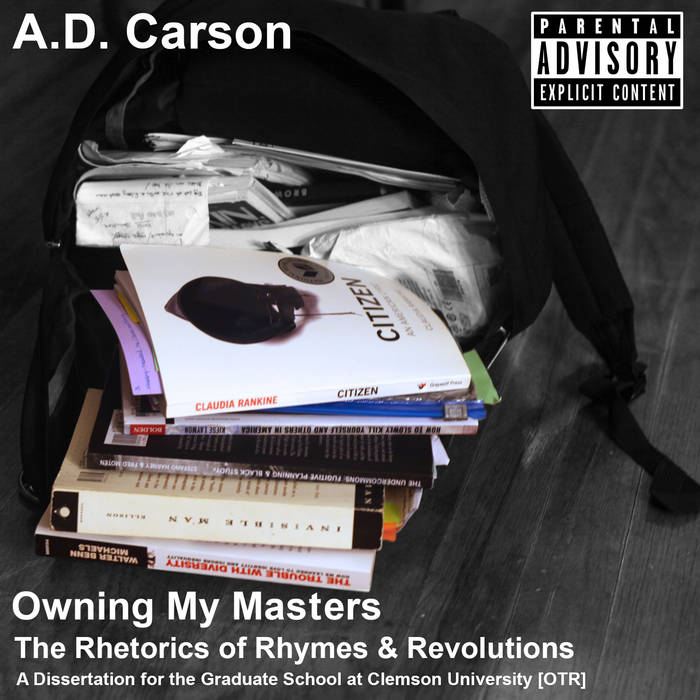

...I released Sleepwalking 2 on Bandcamp on June 22, 2018. The previous year, on September 11, I released Sleepwalking, vol. 1 on the same platform. The projects are extended from my dissertation album, Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions, which was written and recorded over the course of three-and-a-half years during my doctoral program at Clemson University from 2013–2017. After I defended the dissertation and went on the job market, there was still much more I wanted to say. The first Sleepwalking project focused on the time between the dissertation defense and starting my appointment as assistant professor of hip-hop & the Global South at UVA. While it opens with remarks and a poem I delivered at an event the morning of the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville—a performance of "Good Mourning, America," a track from Owning My Masters, and contains an interlude featuring the American president's remarks after everything happened—the contents of the album mostly don't address the events of August 11–12, 2017. It's a project written through the experience of my transition from graduate student in South Carolina to a new job in a new place.

Sleepwalking 2 doesn't deal directly with the so-called Summer of Hate, either. Instead, I wanted to focus on something I felt was obviously related—language and violence. Both Sleepwalking projects deal with the same set of questions I wanted to address with Owning My Masters:

What are the roles of hip-hop performance in knowledge production and what types of ideological work is being done by scholarly engagements with hip-hop performance? How can hip-hop performance resist [or push beyond] the limits set upon it by academic convention? How does one more effectively approach hip hop academically in a manner that speaks through [one of] its form[s] and doesn't reinscribe the "oppression" the form seeks to subvert? How can we responsibly deal with the issue[s] of access [to academic resources: admission to programs, fair compensation, employment, etc.] for producers of cultural products like rap music/lyrics [that are taught, analyzed, and/or evaluated in academic spaces]? How should [or How/Should] our considerations of responsibility regarding access change if the aforementioned cultural products are created by people who have not achieved notoriety, whose works are studied in academic institutions but would likely not qualify, for whatever reasons, to study or teach at those?

These questions were presented with the conjecture:

"Hip-hop studies, while pushing boundaries in many respects, particularly the intersections of many different disciplines, reproduces certain forms of—and assumptions about—knowledge production." I would amend that to include studying hip-hop, which isn't necessarily the same thing as hip-hop studies. And, also, I don't mean hip-hop studies on its own or all of hip-hop studies. "Additionally, some conventions in the discipline and certain types of scholarly performances of hip-hop scholarship render blackness pathological—even in the service of combating what might be understood to be antiblackness, by virtue of attempts to combat the notion that hip-hop culture is, in fact, deviant or bad or unworthy of study. Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions serves as one of many possible explorations and analyses of this broader problem." The Sleepwalking projects are other possible explorations and analyses. In the video introduction to Owning My Masters, I talk about dope—about being the dope and doing the dope (work that is, in my case, rap-writing and album production as scholarship). This, too, is an aim of the Sleepwalking projects.

In an interview with Darryl Robertson from Black Perspectives (published by the African American Intellectual History Society) after I submitted Owning My Masters to the graduate school at Clemson, I was asked how I think my work—dissertation, specifically—will change the way hip hop is assessed by scholars and how I think it will transform the field in general. In response, I stated,

My hope is that the production of hip-hop—writing, music, poetry, art,dance—continues to be counted as, added to, and accepted among the many ways we respond to the pressing questions being asked and addressed in our scholarship. I want to change the politics of knowledge production. It is clear there is much to be appreciated in what hip hop offers to many academic conversations. I do not know that the dissertation calls for transformation so much as it asks what might be gained from opening up those conversations to others who might want to participate by way of these types of offerings of responses to the calls.

The Sleepwalking projects are presented with those same hopes I have for Owning My Masters, which are also hopes for what we might consider social change in a broad sense. The practical ways this change might happen are much more difficult. The listening roundtable is an attempt at this by bringing together scholars in fields related to the work for a listening and discussion session with an audience to see if we might be able to perform a version of this change—through resistance and submission to—academic convention.

"Bear with me."

◆◆◆

2. Njelle Hamilton (Introductions)

Njelle Hamilton: Welcome. Thank you all for being here. I'd like to welcome you all on behalf of The Carter G. Woodson Institute and the McIntire Department of Music, co-sponsors of this listening roundtable. My name is Njelle Hamilton. I'm an assistant professor here in English and African American Ethnic Studies. It's my pleasure and honor to introduce you to this phenomenal roundtable of artists and scholars all gathered this evening to talk about Sleepwalking 2.

[applause]

The exciting, important mixtap/e/ssay by our colleague A.D. Carson, AyDeeTheGreat. So, I'll introduce our panelists, but we'll play the album through—it's about 17, 18 minutes—and then we'll proceed from there.

So we have nametags so you can indicate my colleagues. Professor Jack Hamilton, assistant professor of American Studies and media studies at UVA. He's a cultural historian who studies sound, media, and popular culture. His first book, Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination, brilliant work.

[applause]

...A groundbreaking work on re-centering race in the conversation around rock history. He has won numerous awards and was named by PopMatters—'cause that matters—as one of the top 10 conversation-shifting books about music of the past 10 years.

Audience member: Yah.

Njelle Hamilton: Yeah. It's true. A pop critic for Slate Magazine, his writings appeared in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, NPR, and many other venues, and he's currently working on a book I'm excited to read about music and technology since the 1960s. Jack Hamilton.

Professor Lanice Avery is assistant professor in the Women, Gender, and Sexuality and Psychology departments here at UVA. Her research focuses on Black women's intersectional identities, how the negotiation of dominant gender ideologies and cultural stereotypes are associated with adverse psychological and sexual health outcomes.

Audience member: Hmm.

Njelle Hamilton: Her current project seeks to understand the ways in which gender-based psychological and sociocultural factors inform sexual beliefs, experiences, and health practices of young Black women and it aims to promote healthy gender and sexual development among socially marginalized and stigmatized groups. She also runs RISE—Research, Intersectionality, Sexuality, and Empowerment—lab here at UVA. Lanice Avery.

[applause]

Professor Guthrie "Guy" Ramsey, Jr., is a pianist, composer, and the Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Music at University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of several books on Black music, including Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip Hop and The Transformation of Black Music: The Rhythms, the Songs, and the Ships of the African Diaspora.

As leader of the band "Dr. Guy's MusiQology—"

Audience member: Oh, cute.

Njelle Hamilton: ...he has released three recordings and has performed internationally at legendary venues such as The Blue Note in New York. His documentary film Amazing: The Tests and Triumph of Buddy Powell was a selection of the Black Star Film Festival in 2015. He co-curated the 2010 exhibition Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing: How the Apollo Theater Shaped American Entertainment for the National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian. He is also the founder and editor of the popular blog MusiQology.com and he's now expanding the banner to include a record label, the MusiQ Department at a community arts program called MusiQology RX. Is that how you say it?

Guthrie Ramsey: Yes.

Njelle Hamilton: Yes. MusiQology RX.

[applause]

And last but not least, of course, Marcus "Truth" Fitzgerald. A record producer and recording artist who has appeared on several AyDeeTheGreat tracks. Originally a rapper since 2001, Truth has expanded his craft in the area of production. As a founding member of One Shadow, he has produced and recorded 10 rap albums. One Shadow is known on the streets of Chicago for your rambunctious beats and catchy hooks. Ladies and gentlemen, Truth.

[applause]

"This is the next time, prepare for fire." These opening lines on A.D. Carson's "Good Mourning, America" are a great introduction to and summary of his groundbreaking work as both a hip-hop artist and hip-hop professor. In rap speak, "spitting fire," in Twitter speak, "flames emoji." [laughter] In James Baldwin speak, "the apocalyptic tomorrow where black justice rains down." In A.D. speak, "all of the above," but also the rhetorical now, the now of the hip-hop track, the tempo of the beat, the present of his words that bring historical knowledge to bear a searing critique of white supremacy and its many, many legacies. It's a fire that burns and destroys, also fire that enlightens and awakens.

On Sleepwalking, vol. 1, released September 2017, AyDeeTheGreat cites Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man's meditation on bumping into sleepwalkers and wondering if he should bump them hard enough to wake them. He says, "[S]ometimes it's best not to awaken them. There are few things in this world as dangerous as sleepwalkers." A.D. adds, though, that quote, "I learned in time that it's possible to carry on a fight against them without them realizing it." Some question of methods, of tools, of weapon. Is hip hop that weapon or method? A recognizable method for those who are awake or woke and invisible, dismissible and missable for those who think it's just gibberish.

I'll quote a YouTuber commenting on A.D.'s dissertation intro v ideo—apologies for quoting someone this disturbed and irritated—but it says, "You can get a Ph.D. for gibberish and N-word slinging at Clemson University. The soft bigotry of low expectations."

Audience member: Yay. [laughter]

Njelle Hamilton: Professor A.D. Carson, performer, recording artist, and assistant professor of hip-hop & the Global South here at UVA, earned his Ph.D. in rhetoric and composition [rhetorics, communication, and information design] from Clemson University, not in gibberish, in 2017 to much fanfare. And this is partly because, in lieu of traditional 200-page dissertation, written document, he submitted a 34-track rap album, Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions that made news and fans around the nation.

Upending the academic credentialing in this way, A.D. announced his mastery of the field of rhetoric and composition by centering hip hop as form, as frame to hold the ideas, experiences, testimonies, and critiques that constitute the content of his rap compositions. He also announced his intention to make hip hop occupy space and to use it to contest space within the academy. The space for subaltern art forms, the space for Black politics and poetics. Masters' chiseled cover art announces its erudition in Black scholarship, Claudia Rankine's Citizen, Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, and others stacked so their spines are visible, crammed into a black knapsack and with handwritten notes stuffed between their pages.

On the one hand, a visual representation of the qualifying exams for a Ph.D. On the other, the sonic output that emerges from that literary input. But it's also re-visioning of the titular masters, A.D.'s backpack opens itself up to multiple suggestions, are these Black authors the real masters of rhetoric? The masters who inspired the project, the masters whose revolutionary words about the Black experience he carries on his shoulders, literally, or carries forward?

Now, A.D.'s arrival in Charlottesville coincided with the now-infamous Nazi marches on August 11 and 12, 2017, and culminated in the release of Sleepwalking 1. The events that peeled back the façade of post-racial America underscored the urgency of his work as artist and professor. Sleepwalking 2: a mixtap/e/ssay, the focus of our listening roundtable this evening, continues A.D.'s interrogation of what it means to be woke in this moment.

Like his dissertation album, and scores of term projects in-between, Sleepwalking 2 continues to upend the boundaries between art and scholarship, art and politics, and presumed high and low cultures. It is made visible in its subtitle that it raises the question of where mixtape and rap end, and where essay and scholarship begin. As the opening track attests, words matter, they take on form like sticks and stones that cause harm, no less violent, no less painful for their ephemerality. What's most powerful about A.D.'s work is that wordsmiths like him and other artists before him, take up words making them matter, material, not only as weapons but as shields, wings, and seeds of alternate futures. Ladies and gentleman, A.D. Carson.

[applause]

Njelle Hamilton: And so, we'll proceed, we'll listen to the album and then turn it over to the panelists.

◆◆◆

3. Sleepwalking 2

◆◆◆

4. A.D. Carson

[applause]

Marcus Fitzgerald: Dope album.

[laughter]

A.D. Carson: Appreciate that verse, man. Way to close it out.

...Guthrie Ramsey: So, how would you like to proceed?

A.D. Carson: Um. [laughter] That's a great question. I think we just start up here, so I don't know.

Guthrie Ramsey: Maybe a statement would be in order.

A.D. Carson: Yeah, okay, so, yeah, so I think a few things is that I was very intentional in wanting to make the album digestible in... one sitting. So I thought that the previous project was 12 tracks, and the one before that was 34, and I felt in both of those instances, there were lots of things that I never really was able to get to in conversations with folks, even though they felt like they were entire projects. And some of it was that there were a lot of things that I was trying to accomplish with just like one track, and so, if I'm talking to folks, then I end up talking about that one thing and then that takes up all of the time.

So, if I was to try to, like, scale back and then to not really change the way that I'm making the individual pieces but to make the comprehensive piece something that was, at least you have the time to sit through, and then have a conversation, then the conversation to be about the entire thing rather than saying, "let's take this one piece," and then have, you know, a whole bunch of conversation around that. And then I would feel a little more satisfied with like what could be accomplished in the time.

So that has more to do with the desire to make something that was less than 20 minutes more than anything else. It's just to be able to let it do whatever it needed to do within the space of time, if it's a 50-minute class we got 30 minutes to talk.

Audience member: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Marcus Fitzgerald: I appreciate that, I prefer the short, [laughter] short conscious, digestible, that's what's been happening. When our best friend Kanye [laughter] recently released his three new projects. They were short, people were beating up on him for his political stance and all that but I still appreciated the fact that they short digestible projects and so I, that's what I got from this project, and that I can listen to it and actually provide feedback on each and every joint.

A.D. Carson: Yeah. It also sucks to record 34 tracks and then like you play track 28 and somebody's like, "Oh, you put new music out." [laughter] Word. Word. That's the deep cuts.

Njelle Hamilton: Do you want to move down the line and respond to whatever comes to mind, what part of this made—

A.D. Carson: Sure. Oh.

5. Guthrie "Guy" Ramsey

Njelle Hamilton: ...Guy.

Guthrie Ramsey: Okay, I'll start. First of all, congratulations—

A.D. Carson: Thank you.

...Guthrie Ramsey: ...on just everything. I've read the press and I've listened to a lot of the work and it is, you are well on your way to create a body of work that I think is going to be very impactful.

A.D. Carson: Thank you.

Guthrie Ramsey: Let's start with the length, that's a way to get into it, because I always, as a musician that, I always begin with the sonic element and then move—you know. I could listen to this piece and try to learn it 20 times before I even get to what you're actually saying in the piece. So that's just my orientation into sound organization because I think when we talk about what this piece is about, it's necessarily contained to the truth claim of the lyrics.

A.D. Carson: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Guthrie Ramsey: It's about a lot of things. So, I loved you talking about the length of the project as something that could be heard and then discussed in a classroom.

A.D. Carson: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Guthrie Ramsey: I can't think of anybody in the hip-hop world who creates art in that context.

Audience member: Hilarious.

Guthrie Ramsey: Which is a good thing.

A.D. Carson: Yeah, yeah.

Guthrie Ramsey: You know what I mean? So, there's a practical side to that as a professor, you want to be able to, we have, I mean this is labor so we have a time frame.

A.D. Carson: Right.

Guthrie Ramsey: And you know if the class is 50 minutes, minute 48 those students are zipping up backpacks, [laughter] closing their Facebook accounts, [laughter] you know, they get ready to break. Okay. So, it's really fascinating to hear it like that, but let's think about it, you know, I have so much to say, cut me off. Okay, so just let's move out further into what this piece is doing for you and the kind of trajectory of a career.

A.D. Carson: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Guthrie Ramsey: And just as I think about young professors as yourself, you know, I'm just always sizing you up because I know if it's Black music, more often that not, that tenure case is gonna come across my desk.

A.D. Carson: Word.

Guthrie Ramsey: And I'll have to make a case, okay, for why this is interfacing with the academy at this time and this place and what is, is important. So the usual trajectory for professors and after reading your press, you know, the thing that they're going nuts over, oh he had, he made a recording as a dissertation. And that's what the outside world is going bonkers about, but on the inside, we know that D.M.A.s make music to get Ph.D.s all the time, okay. So that's not unusual, what is unusual is that the piece itself is not a written score.

Guthrie Ramsey: So, in the usual world of music studies, what circulates for your tenure case is the score and a recording, not just a recording. Because if it's just a recording there's this idea that it's less rigorous, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, dot, dot, dot. And just insert that stupid YouTube comment that you read.

[laughter]

Guthrie Ramsey: So that's where that's all coming from, right? This is where they're saying 'cause there's less cache and some organization presented as itself being the raison d'être for the career. So that's one way that you're really pushing against, you know, the grain here but let's think about, okay, that's the first comment.

Guthrie Ramsey: Now let's get right into sound organization which really is where I think is the straw turning the drink here. I sense in your work there's this subversion of verse/chorus structure, okay? It's almost as if each piece is through composed lyrically which announces straight off the bat that this is not trying to be in the market, you're not trying to win a Grammy with this because it's obliterating all of the rules of good songwriting that Irving Berlin put out in the 1920s, okay? Which still wins Grammys by the way.

Guthrie Ramsey: Then there is your flow, which is somewhat idiosyncratic because what I notice is that its relationship to the beat is like you're aware of the aura of the beat but you're not contained to this, you know, kind of isometric declamation to it, so I guess there's this sense of freedom that you're, it almost announces that you are not trying to trance listeners but you are really calling attention to the lyrics' past literature and not simply as a hook that you want be an earworm.

A.D. Carson: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Guthrie Ramsey: You know? Whereas you could wash dishes and still be cooking, okay? So that's the other thing. Another thing that I noticed is that there are two kind of vibes that you go for in terms of the tracks. There is definitely a 1990s vibe which I wanna talk to you about, which I hope you can talk to us about in terms of how the beats are organized. But then, there's this lo-fi thing that you do in that second-to-last track, which is really kind of puts it in this, this is historical conversation going on between those two kinds of beat worlds, and then finally, there is this lack of rhythm and couplets in the work whereas you're not necessarily trying to rhyme couplets, is what I mean.

Guthrie Ramsey: There's this lack of rhymed couplets in it that, you know, kind of pushes it in a more avant-garde direction than a lot of what we hear in, even classic hip-hop, you know, the best rappers, rhymed couplets is the name of the game, you know? But you, kind of, you withhold that from us, so let's can we just start there and, uh... [laughter] I told y'all I didn't want to go no first!

Njelle Hamilton: Well, do you want us to just kind of take comments and then A.D. can process, if you wanna respond a little bit.

Lanice Avery: Folks want answers.

Njelle Hamilton: Before you forget.

A.D. Carson: Respond? Well, um, yeah, the... so like the relationship of the beats, there is this, um... I'm trying to answer without like... No, that's a thing, that's a thing. [laughter] I'll say that. It's a thing, it's intentional. And my relationship rhymewise to that and I mean, Truth will probably talk more about this, like how do you, like what does it mean to, like the expectation and the payoff for a listener in a verse and then what that does to, um, trick the listener...

Guthrie Ramsey: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

A.D. Carson: ...into listening for the thing that have been taught to expect—

Guthrie Ramsey: Yes.

A.D. Carson: ...in the writing of rap. We listen to enough rap like we listen to enough rap to know that, you know, like when I say, you know, "I'm a really cool cat," if I say I'ma hit you with a—

Audience member: A baseball bat.

A.D. Carson: So, folks kind of understand that and I say, you know, "I'm a hit you with the jack of a crowbar..." and sort of enjamb that and go to another thing, I rhymed. I did the thing, but I didn't do it the way that you expected and so now you're like, "That's not what—that's not what I paid for. [laughter] That's not what I showed up for."

Marcus Fitzgerald: Right.

A.D. Carson: And then when that happens, I think that hopefully an audience is listening, expecting the next time you come and it's like "today was a really good day" and then, "tomorrow I'm gonna go outside, and..." Then like everybody's listening like... and then you do the next thing. I think that that's a very, it's an interesting thing to attempt to do, especially if you're trying to tell stories or if there is like some other intent behind what might be going on in—

Guthrie Ramsey: It's rhetorical, in other words.

A.D. Carson: Yes.

Guthrie Ramsey: It's rhetorical, yes.

6. Jack Hamilton

A.D. Carson: Yeah. Go ahead, Jack.

Jack Hamilton: Yeah, I mean, first of all this is great, also I think Guy just wrote your tenure letter so, congrats.

[laughter]

...No, I fear my observations or questions are not gonna be nearly as perceptive. But, well two questions and one of which actually does move off what Guy was bringing up and then like, which is, like I'm really interested in the relationship between the production and the lyrics and sort of like how, you know, and I'm interested in sort of like the way sort of collaboration functions in terms of the sort of putting the actual tracks together and the selection of the tracks. Because one of the things I was struck by is like, you know "Kill Whitey" has a track that sounds like sort of like a, it's a club track. You know? It's got the trap high hats and like—

Lanice Avery: That's your hook right there.

[laughter]

Jack Hamilton: Yeah, totally. That's like, that sounds like the hit, which is really interesting. And then yeah, the track immediately afterwards it's like, yeah, as Guy said, has that more sort of lo-fi kind of like backpacky, like it started reminding me of like Madlib's stuff from the late [19]90s. And it's beautiful and it works so well with what you're talking about lyrically.

And then the second question, so that would be my first question just sort of like how you go about sort of like selecting the sort of musical backdrops?

And the second one is kind of related, which is sequencing and how you decided to, 'cause one of the things that's interesting, I think, with a album of this length, it's five tracks, you know the order of how you're putting those five tracks together... On one hand, you've only got five tracks but on the other hand the order in which they come becomes potentially all the more powerful in terms of the structure so, especially since you framed it as sort of a mixtape/essay so it's sort of like how the, yeah, how you decided to sequence the tracks in terms of the order?

Guthrie Ramsey: It's a good sequence, yeah.

Jack Hamilton: Yeah.

A.D. Carson: Yeah, so I think that it was after, and there were more songs than those that were recorded, and then it was like so how do we construct a project out of this in thinking about the essay format? And it's like well five components, then we would have like an introduction and a conclusion and then the other stuff make up the body and then you think about, like, what "Sticks and Stones" says and what "Escape" says and then like what "Antidote," "Kill Whitey," and "Concern" do.

And I think that they're doing different kinds of the same work. And that was deliberate after all of the tracks were written to frame them in that way, so that we were at least making, sort of gesturing at performing an essay. In 17 minutes.

Like that collaborative process, I knew, so in writing a song like "Kill Whitey," because the song is "Kill Whitey," that had to be the thing. I mean, I think that it's absolutely hilarious to think about somebody playing that song at the club and it's like, you know, like, "By request— [laughter] everybody wants to hear it again, 'Kill Whitey.'" And then it comes on and it kind of does that thing, and that was intentional, like if there's a hook that is infectious and people, if I could get people to say...

"If he wanna see me dead, ain't no getting in my head, I'm a get..." and so long as I can get somebody to sing that and not care what it's actually saying, and it really doesn't even matter what the words are but the words here are like, "I would love to kill white supremacy." And I don't know, that's a noble cause to get like, to make that an earworm is like the death of white supremacy.

Guthrie Ramsey: It's better than "God's plan, God's plan, God's plan."

[laughter]

[inaudible singing]

A.D. Carson: Yeah, so that was, so it's like deliberate that, you know, like to make the thing that is doing, like, that's trying to do the heaviest lifting, a thing that is also going to be most accessible.

Guthrie Ramsey: Most accessible. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

A.D. Carson: Yeah.

Guthrie Ramsey: Love that tension. Yeah.

A.D. Carson: And then, the others like "Concern," I just felt like it made me feel off.

You know, to have that come after something that is, like I mean we're talking like the grid, to have something that's so snapped, like locked to the grid, followed by something that is merely suggesting that a grid exists is kind of important to create like this, like it's like you sort of slid off of this thing. It was fun while it lasted, now we're in sort of like something that is beyond tragedy and that's like... apathy, I guess. That folks simply don't care what comes on the other side of this violence.

Um, So that was kind of what I was thinking about with that and that is, I think, the difference between Preme and Ryan. And Ryan Maguire did the fourth track, Preme did the second and third. Yeah.

7. Lanice Avery

Njelle Hamilton: Lanice.

Lanice Avery: I have a lot of questions.

A.D. Carson: Word.

[laughter]

...Lanice Avery: Which feels like a nice shift given that we've talked so much about sonic structure. I'm supremely a lyrics girl—

A.D. Carson: Word.

Lanice Avery: ...and I was so excited and generally am so excited because, make no mistake, you are a theorist and all of the content is sort of bridging in these little nuggets of theory, so I have a platform for it and was so upset that there was only one lyrical video because part of what you're doing is, you are a wordsmith, a master without using that terminology, wordsmith. And the way that you play on words is phenomenal and happens throughout and so I think, I had the pleasure of serving on a panel with you and recognize we were drawing from a lot of Critical Race and what I would call Black Feminist Theory and was like, oh, you're my contemporary, brother. Like, I'm here for this.

[laughter]

So, when I came into this project I was really like, it feels like I just want to go into a corner and listen and listen hard and I had to listen multiple times to get through the beauty of the sonic landscape and dig into the texture of your prose. So, I wanted to ask a couple of questions and I have organized them by song.

A.D. Carson: Okay.

Lanice Avery: So, thinking about "Sticks and Stones," specifically how you open, which feels a lot like "Concern," and I will link those two things together. You're talking about this relationship that you have to teaching the children, so whomever those children are, right? And whatever that looks like. And you make this, you say this line, you say, "They'll meet one another with a familial greeting that's passed down through years and they'll all know that they only thing that's never been able to rise above them, like that there's nothing that can ever defeat them."

After sort of talking about how we learn to wield our words and use them in ways that sort of up the ante to beat them at their own game and it made me think of Audre Lorde's "Eye to Eye" in terms of what do we actually inherit inter-generationally? What are the messages, right? Of pain, of oppression, and what can we really learn from being able to think through what these words are? And so I sort of pulled this text note, I'll just read this little short area that's really kind of combing through the whole piece from Sister Outsider, "Eye to Eye," she says, "We as Black women are born into a society that's entrenched with loathing and contempt for whatever is Black and female that we're growing, eventually every human," excuse me, "that we're growing up and metabolizing hatred like daily bread, which means that eventually every human interaction becomes tainted with the negative passion and intensity of its byproducts, which are anger and cruelty."

"And that this cruelty between us, this harshness, is a piece of the legacy of hate with which we were inoculated from the time that we were born by those who intended it to be an injection of death. But we adapted, learned to take it in, use it unscrutinized." And so, my question for you is have you considered the ways that metabolizing hatred like daily bread and then using it unscrutinized might be the familial greeting that is actually passed down? How do you imagine that our resilience and our imperviousness is actually steeped in intergenerational practices that are not generative or sustaining at all?

A.D. Carson: Yeah, that's, [laughter] yeah, yeah, yeah. No, I think that, yes, like the, so there's this, I mean, I think it's probab—it's fairly easy to say like there's a sample from like, so track two and three, there's a sample of a deleted scene from Boyz n the Hood.

Guthrie Ramsey: Right.

A.D. Carson: And I think that if you're somebody, like, who grew up with Boyz n the Hood, I remember this situation where I was like in my, after my first year at Clemson in this, in the doctoral program I went to Switzerland and then I was, some folks were like, "Let's watch a movie" and "Let's watch a movie that none of us have seen." And I'm like, "We should watch Boyz n the Hood."

Lanice Avery: You're like, "You've never seen it."

A.D. Carson: You've never seen it, no and nobody had seen it, so then I put the movie on and folks were like, "This is ridiculous."

Lanice Avery: Oh.

A.D. Carson: Like it was so absurd, the film. It was, I mean absurd because it was so violent, it's like "This, somebody made this up." And I'm like, "No, no. Actually, where I'm from..." And then folks started looking at me like I was fucked up. Not only, like not because I, because I got some pleasure from sharing with them what to them was the most absurd, cartoonish, like, absolute violence. And folks were like, "I can't believe that this is, not only can I not believe this is a thing, but you would show this to people for pleasure?" And I'm like, well now I'm like—

Guthrie Ramsey: How American.

A.D. Carson: ...well yeah, but then I'm like, "Well this is how we get down." Now I don't wanna watch it anymore. I feel called out and I feel out of place, so like to imagine writing, again, like those tracks in the middle, to comment on that, how do you use the poison to make the antidote?

And so there it's like me taking the deleted scenes from that piece and putting it at the beginning of one that is just so easily readable where these two guys are narrating these circumstances where you're led to believe that one ultimately murders the other and then the one that comes after is like this club thing that's going on and where I just pitched it down and it's the same damn sample that's happening at the beginning of that.

But the sample is like where Furious is talking to Doughboy right before all of the stuff happens and then, um, Furious is grabbing him and he's like, you know, like, "You need to stop. That's exactly what they want you to do." And he's like, "Who the fuck is they?" And then he snatches away from him and then walks off the porch and then we all understand what happens next if we've seen the movie. But that's like deleted from the film so it's recognizable to folks who know the film but if you haven't seen the deleted scenes it's like where in this movie does this come from, it's like taking a memory that you don't know you have and then like using that memory to make you, to evoke a thing that is literally not there.

If you haven't seen the special edition, you don't have that memory, you know the characters, you know the plot, but you don't know this particular scene. And so, using that to construct this, like, you know, the, well part of the body of this argument that's being made and then "Concern" then like sort of speaks to an aftermath of that.

Lanice Avery: I'm really, like, writing my, you're speaking directly to my engagement with the piece because I feel like I understand that as a possibility and also it is inherently flawed as a practice and I think when you were writing "Kill Whitey" and you're saying, "I'm normally peaceful." It made me think about Toni Morrison in Beloved when she goes on to talk about how white folks have sort of created this relationship to what they imagine is this demon jungle inside of Blackness but it is truly their own selves, right? And so by your relationship to becoming approximal to that, even in order to "Kill Whitey" you end up enacting harm.

And so it was no— it was really interesting to me that you followed that with "Concern" and you're talking about, you know, and that you wrote it in 2017 which was when the CDC report and the UN statement came out talking about that like 53% of murders that Black women under 45 are by their intimate partners that are Black men. And so, and that that's the real gun violence that we're not talking about. And so, you're going in to talk about what does it mean to co-opt to utilize without scrutiny that the way to survival is to embrace and embody this violence and wield it harder against white supremacy, but that Black women end up being the casualty of that.

And so, when you come in, and at the end you're talking about that you want your mind back, it's like you can't back to where? And at what cost, right? And then are the Black women's bodies just the byproduct of your engagement with white supremacy and the battle to restore yourself and then how might you think about, then, that as a freedom practice as a strategy?

Like what is the philosophy of freedom if it is about utilizing the poison as the antidote?

A.D. Carson: Yeah. Yeah. I think that that, for sure this, like specifically, um, "Escape" and, um, then the questions, like escaping to where? And my hope at the end, like the reason that that like I just kind of, there's this filter at the end that kind of like sort of muffles the entire thing and then just smothers it out. And for me that was very intentional. It's like, yeah, this thing is unresolved, um, is fatally flawed, and yet it's like the imagination leads you there as the thing that, like as the imagination leads you there as the possibility and like that's also responded to as impossible.

Like the thing that you are imagining, like, the very idea like writing the song "Kill Whitey" can't really exist in this space, while employed at this place, you know, and engaging with colleagues or just folks who are like, "But he wrote this song about murdering us."

Lanice Avery: But if you can't murder Whitey then are you murdering Black women inst—

A.D. Carson: Yeah.

Lanice Avery: Because that's what you can do.

A.D. Carson: Well—

Lanice Avery: And then when is the concern evident in that place? Because I think part of your language is about an us, a ubiquitous us.

A.D. Carson: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Lanice Avery: And the angst that we all sort of have that there's a gendered relationship to that us.

A.D. Carson: Yes.

Lanice Avery: And what does it mean? Like, where does that go? What is the concern? What is the, like, breaking... and specifically how might all of that be oriented toward the message that you're sort of offering up to these children who are captive audiences and sort of listening to that piece? Also telling you, right? We have so many queer and young folks who are always writing the way out, right?

And so, while you're talking about this, this language of, like, "I'm gonna give you this thing and these wings that you will then know." Like what are you taking up from what they are telling you when you're revising the strategy of freedom?

A.D. Carson: Yeah. That's—

Njelle Hamilton: I want to get in and bring Truth into this conversation.

A.D. Carson: Okay. Yeah, no I think I have to sit with that, I don't know, I really like I don't, yeah, I don't know what the, um, I don't have an answer.

Audience member: That's fair.

Lanice Avery: Maybe there's no answer.

A.D. Carson: No, yeah, I mean, I wish that I did. I know that there's always this, um, this—the desire to attempt to even think about practices that other folks might take up. Like even if the content may not be the path, the content that I provide may not be the path because of the limitations of my experience. And so, you know, because the fact, the way that, the practice that creates this album looks different in a classroom, you know? It looks different because the content is actually coming from the folks whose experiences are going to play out in the thing that they make, which is also an incredibly difficult thing when you are the person who's given the authority to sort of oversee whatever that might look like.

I mean, even today folks are asking, "Well, what is the content of the thing that we make, what are we allowed to do?" And I'm like, "That's not even a question that I can answer. Do the thing that you are moved to do." And, but then I'm having to ask that question of the students when they do the thing that they're doing, and I'm like, "But what are the implications of what you do here?" You know like, "Who is harmed by this particular enactment of these, you know, practices that you are performing?" and just asking to consider, you know, what that might look like. And it's a hard space to really think around and by the time that we're in a point, in a space to like, in a space to consider the thing that might've been done, like the terrible thing that might've been done, it's likely happened.

Like we're sort of revising to say "I didn't mean to do that" or "I didn't mean it that way" or, you know, like, "I was trying my best," and then we're talking about intentions, which you know does nothing for the person who's harmed is like telling them that you didn't mean to. Yeah, that's heavy.

8. Marcus "Truth" Fitzgerald

Njelle Hamilton: So Truth, so you're on, you're featured on "Escape."

Marcus Fitzgerald: Yeah, I'm featured on "Escape." With me, I'm more like a vibe person, you know, I don't look at, I can get the title, and I got the verse from A.D., and I guess the drama of beat and I pulled some extractions from what he was saying, basically just talking about how, in my mind, we're sort of algorithms, right? We're just a resulting of what we see and what we've been taught, the media and different things like that. And at this moment on this record what I felt is that I recognize at this certain moment where I'm like, "Wow I'm part of an algorithm. Everything I'm doing has been controlled, and me and my partner, my friend from Eastern Illinois that I used to rap with, I'm gon' try to figure out where he's at in this algorithm that we've been living in." That's why I have a part of my verse where I'm like, "Dilla, you out? Like—"

...A.D. Carson: Yeah.

Marcus Fitzgerald: "...you be teaching that in University of Virginia, expressing exactly what we used to talk about as kids, your mind has not been shaped and twisted like mine was at that point." You know, and this was, this is me reaching out to you and saying, "Hey, I recognize that and I want some of that and I wanna be a part of that." So, that's what making "Escape" was to me.

A.D. Carson Yeah, and that, the sample, I don't know if anybody recognized the sample from "Escape." Uh, any fans of, uh, musicals, nah?

Guthrie Ramsey: Put it on again and let's see. Anyway, yeah, but—

A.D. Carson: Nah, yeah, it's, naw, it's from Wicked It's like...

Lanice Avery: Oh, hilarious.

A.D. Carson:"Who Mourns—Mourns for the Wicked."

Jack Hamilton: Like, the horns? The horn part thing?

A.D. Carson: Yeah, so that's also that, yeah, anyway that's just like a small footnote. Thank Preme for that.

9. Roundtable Discussion

Njelle Hamilton: Is there a sense though, I could be maybe pulling some of the comments together before we turn to audience questions, um, that for you, right, he's escaped but kind of earlier, A.D., you mentioned that sort of your ways you're constrained, one, by the "master" format and your desire, right, to kind of reach this generation here, right? But also constrained perhaps by being "the Hip-Hop Professor," right?

A.D. Carson: Yeah.

Njelle Hamilton Is there a sense of yes, freedom, right? With where you are now but also other than you were kind of—

...A.D. Carson: Yeah, I don't, again, 'cause I don't really see it as, like, so it's like the desire for it but also realizing that ultimately it's not the thing. Like that it's not really sort of like out, you know, that there's this, there is this incredible violence that kind of exists in the space that, um... that kind of like...

So, I remember writing when thinking about how this thing is going to be organized and someone, like more than one person commented that, like "Sticks and Stones" is far more optimistic than I am anywhere else in my life—ever.

And normally that's not it, I'm like well the only place that that could be I think it would be dishonest end the album "Sticks and Stones."

Lanice Avery: Hmm. Interesting.

A.D. Carson: I felt that way. That like to presume that you're going to fashion these wings and then like somehow, like, "Naw that's not it." So, if you put that there at the beginning and then sort of work backward, then "Escape" is sort of like going back into it. It's not actually getting out of it. That, so that's the worry. It's like going to UVA wasn't like, I didn't escape, like, I landed on a plantation.

Lanice Avery: Listen.

A.D. Carson: You know, like that's, again. Again. So—

Lanice Avery: Yes, what a metaphor!

Guthrie Ramsey: I have to ask this question because, I mean, I have questions about the role and purpose of art.

Lanice Avery: Oh. [laughter]

Guthrie Ramsey: Because, just as someone who writes music, and someone who explains music for a living because the music that I make does not feed me [laughter] as most musicians, you know what I mean, so it's like a luxury to be paid for it, so you must be making it for other reasons. When I teach, I'm always making sure that students understand that art is not always meant to be didactic.

A.D. Carson: Yeah.

Guthrie Ramsey: That art has to somehow be relieved of the burden of truth, no one asks Stephen King about what the role, you know, what is this? What good is this doing or any other, I mean, it's only in music where we collapse lived experience and the artistic convention.

Jack Hamilton: Particularly hip-hop, I would say.

Guthrie Ramsey: Particularly hip-hop. Yeah man. And so I'm... if we look at your work as theory, you know, which is meant to explain some phenomenon in the world or help us understand patterns of phenomena in the world and not simply, because this is the direction we're going that this is supposed to be solving some kind of world problem or, you know, rather than a clever use, so when I think about you, I wrote the word "cinematic" down.

That your work has this aural, you know, cinematic. The sound of it reminds me of that and is that not enough meaning? Could that be enough meaning? You know? You know what I mean? And I loved your reading of it and how, you know, to go to Audre Lorde, I really love that which means that this art can speak to many people in many ways and it doesn't have to be a way that it has to be in the world. Or, I'm asking you, or is there some specific thing that you are going for when you write, or you know, or is it just the play of language. You're a rhetorician.

Guthrie Ramsey: You're, I don't look at you as "the Hip-Hop..." I hate that "Hip-Hop Professor." I hate when people call me "the Jazz Professor." It's like, how come my white colleague can be a musicologist—

Lanice Avery: You know why. You know why.

Guthrie Ramsey: You know, that was rhetorical as well. [laughter] You know what I mean, it's sort of like this idea that they're trying to market something that's been here a long time and it's, I'm getting a little confused.

A.D. Carson: Yeah, naw, so yeah that's not, "the Hip-Hop Professor," that's not my thing. [laughter] That's not my thing. That's here. I mean, that's the title. That is the thing, so there's that. The, like with the question, I mean I think that, so to try to address Lanice's questions is like me answering her questions specifically and not really trying to determine, like, the albums, like what the album does.

Guthrie Ramsey: Got it.

A.D. Carson: It's like I'm answering her question about her reading. So, I would hate to sort of put that forward and say, "This is what this album is doing," because then that would be dishonest.

Guthrie Ramsey: Okay.

A.D. Carson: But it is a response to a question that's generated from a listening or several listenings. Yeah, and I think that that is kind of the work of the art is to generate that kind of thing and part of the purpose in gathering folks from multiple backgrounds to get those kinds of questions that many of us are going to, like they kind of come to conflict because of the disciplines that, like, you know, like these the literatures that we read or the arts that we engage lead us, like bring us to this spot and then we engage whatever it is in front of us through that filter. So, for me I think that that's really important because I'm attempting to do a lot of these different things whenever I'm writing.

Guthrie Ramsey: Right.

A.D. Carson: There's a world of music that I'm thinking about, there's like the generational thing, there's a geographical sonic thing that I'm attempting to go for.

Guthrie Ramsey: Yeah.

A.D. Carson: But then there are all these people that I'm reading and then I'm trying to think alongside in doing that kind of work as well. And so—

Guthrie Ramsey: They're not mutually exclusive.

A.D. Carson: No, and so it's, there has to be an ability to at least respond to the question but if somebody says, "Well what is the specific work of this album?" then like my answer to that would be much different.

Guthrie Ramsey: Yes.

A.D. Carson: But because this is, I mean, a question I can answer that question because it's just like that was nowhere on my radar then I could probably say, "That's nowhere on my radar and I'm not in dialogue with none of that, that's not even what I'm trying to do."

Guthrie Ramsey: But you can't control that because—

A.D. Carson: I can't.

Guthrie Ramsey: ...the art goes out and people just, they circle around and just—

A.D. Carson: But I think that, but there is an attempt, however, to, I mean, again trying to write, like knowing that there will be these readings because you know enough of the literature or that you're signifying enough that folks who know that literature, like that's what you're doing. Like that's not coincidental that you're doing that, so it's not like a coincidental, like someone coincidentally arriving at this particular reading.

Now, if somebody does end up at a certain spot and then I'm like, "Yo, I don't know how you got there. Your GPS took you there. But that's like definitely not what I had programmed."

Lanice Avery: You need an update. That doesn't even exist.

A.D. Carson: Then that happens and I can be honest about that as well.

Guthrie Ramsey: Just "nope."

A.D. Carson: But I don't wanna take any of that away from folks, so I don't wanna like put, you know try to apply some language to it and say this is the thing that was going on. If you don't read it this way then you missed it.

Guthrie Ramsey: No, no understood.

A.D. Carson: And that's why, you know, very often with those prefacing remarks it's just like, okay so here's some things that I knew I was trying to do.

Guthrie Ramsey: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

A.D. Carson: And that's it. You know. You look like you was about to say something, Truth.

Marcus Fitzgerald: Yeah, I was just saying that if, even after you explained the song, that's not what I knew when you sent me the verse.

A.D. Carson: Yeah.

Marcus Fitzgerald: I got the track and the verse and I just got a feeling and I'm like, okay, he escapin' from somethin'—

A.D. Carson: Yeah.

Marcus Fitzgerald: ...and he rhyming like this, this is dramatic and let me hop on that and let me talk about my experience of escaping and what I'm interpreting from it. And then after time, me and he will have conversations and maybe two years later we'll be like, "Oh, that's what you was talking about in that?" [laughter] But it's really just a sense of the vibe that you get as a, at least from my standpoint as a rapper and producer, it sparks that initial energy and then you go back later and you say, "I was in this space at this point and this is exactly what my goal was when I was writing this record."

A.D. Carson: Also, I had another friend who is an emcee who works at another university who, um, you know, we collaborated on something and he's like, "You know it's always interesting writing a song, like when we write a song because I don't know what it's gonna be until it's finished."

Marcus Fitzgerald: Right.

A.D. Carson: And then I'm like, well this is like for me, it's a learning process. I don't know what we're doing until we're done. So I have these thoughts about what I want to accomplish but this is like me inviting Truth into a conversation with me about this thing and then like his take on it is like him, is like me like sort of handing him the vehicle and then he's driving. And so I got, you know, halfway to a spot and was like, "Here's the steering wheel, if you wanna get out and look at the car and see what it looks like, then you could talk about that if you'd like or you could take us to another destination."

Guthrie Ramsey: That's cool, man.

Marcus Fitzgerald: Anything else would be wack to me. [laughter] If he was like, "I was writing exactly about this, now I want you to be this character," then I'm dead lyrically. I'm like, "Ah I didn't want to be that character, I wanna be Truth in this position, I wanna talk about this on this track." But of course you don't wanna talk about two different things. I didn't want to come here talking about a totally different subject. You give the beat, you give the title, and then you just, you vibe out.

A.D. Carson: And that happened with Preme as well to try to like, like "Antidote" was an entirely different thing when we sat down. We were in the room together, like, he came here last year to do a workshop with some of my students and then we were sitting there like really, it's like well what's the story, who are these people?" And we didn't know what was gonna happen to the people. We really didn't know what was gonna happen to those two dudes who were in these two different spots. Um, and I just knew, "We lived all over, but my pops he lived on Wood Street."

Marcus Fitzgerald: Wood, hey.

A.D. Carson: He lived on Wood Street. "I always heard, 'I ain't no killer but don't push me.'"

Marcus Fitzgerald: Yeah.

A.D. Carson: And that was like, nope. So that was the thing, that was the thing that stuck and then and he starts off his verse like "Grew up around the way." And then we go to this point where these two people meet and it so happens that it ends the way that it does, but that wasn't a thing that was predetermined. We arrived kind of at that together. Yeah.

10. Audience Q&A

Njelle Hamilton: Can we answer questions from the audience, take your questions? Questions or comments?

[laughter]

...Audience member: You mentioned the word subversion and that word kind of like impacted me and sort of kind of gave like a thematic coherence to everything that there's a sort of subversion of the rhyming couplets, there's this subversion of idiomatic expressions where you're getting this earworm and then using it to communicate something completely different than you would expect and especially in "Kill Whitey" you have this subversion of this derogatory offensive word that when people hear it, especially a lot of white people, they'll like shut down and like, oh I don't wanna listen to this I don't wanna, you know. And it's sort of like you're missing the point that there's so many other things to be offended by, so it's sort of like using this kind of message and, yeah, so I thought that subversion was really thematically coherent across like lyrics, content, music, like all of it, yeah.

A.D. Carson: I appreciate that. Also, it felt like it wasn't overkill to say like to literally say that song is like you're hearing something else when you listen to this because it is so potentially offensive that folks will just hear the thing that they're offended by and then go with that, even if you're telling them, "But it's not that, I promise."

Audience member: So, I wanted to pick up on this last conversation you and Truth were having about the idea that there are these certain types of human actions that are seems like free, you have no idea what's gonna, how they're gonna end before we start them. That's really cool form of human relationships. I think it's really neat that we can do these sort of things that don't have structure come into being as you start to talk to each other. What I'm wondering is like whether, so I gotta just like a thing that I'm super interested in. I wonder whether the fact that there's social matters there or where there's the like when you're just writing tracks on your own whether there's that same sort of lack of an end point.

Marcus Fitzgerald: For me, it's always, it starts off as just a feeling and a title, but at the end my goal is always to make sense of the end of the verse. I don't wanna just put out something that doesn't have a middle and an end, so I feel like I, me personally I feel like told a beginning, middle and an end and that it's not just ambiguous and that it is an escape point from my stand point, I feel like I captured it from that standpoint. I extract the same thing from A.D.'s verse but it does start off as just a feeling and that's the funness of creating hip-hop tracks is that you can just start with a vibe and then as you writing it, it kind of increases as you write the verse and then you go back and you start to read the beginning again and say, "Ok, let me make this and make sure that this verse makes sense." And sometimes it comes organically, you don't really have to work to do that, you know, if you're a pretty good writer.

A.D. Carson: I think sometimes things age differently, you know? Like there's thing that I intended and I wanted it to do a particular thing and so then time passes and the world has changed but the piece hasn't and so the piece means something different because of how we get along with each other since the piece came into existence and I've had that happen. I remember writing a thing down in Clemson. It was a song called "Willie Revisited," which is like essentially about or at least a response to the so-called "Willie Lynch letter" and at one point I thought this song is about like the world of rap.

A.D. Carson: It's about all of these rappers who are doing this terrible thing and one day as I'm walking across campus, if you know Clemson is a plantation too. As I'm walking across campus I started feeling like, "This song is about you!" Like I feel convicted by these words that I wrote that I thought I was writing about other people as a critique of this thing and it's like "Dude, you are not outside the thing. Actually, you embody the thing!" And then it started being about me and I'm like "Yo, I came for myself."

[laughter]

And I felt like really done in by it and sort of embarrassed like that this song was like that I thought, that like—

Guthrie Ramseay: It's sort of like what you were talking about—

Lanice Avery: Thank you very much.

A.D. Carson: So yeah, that happens a lot when I think, yeah, I'm doing this thing that I'm able to speak but some kind of, like, that I can speak from the outside of and then I realize that, "You keep thinking that there's an outside."

Lanice Avery: Listen.

Audience member: Yeah, I think, to that point I think it relates to something that you had mentioned earlier as well in the roundtable discussion about kind of being within and without some sort of larger body that we may not understand who is being harmed by the actions of liberation or what have you. So I think, by virtue of being a student of yours as well, just kind of listening to the work, the thing that resonates with me the most is that, you know, we are all agents of these institutions that we claim to be subverting and simultaneously we embody what it is that the institution wants us to carry along because the purpose of the institution is to, I guess what is the word? Perpetuate, to stay alive so as we are going through it, even as students at UVA, we're taught so many different things, you know? "This is how you can resist these norms, and you know, what have you," and yet a lot of us are punished for doing these things that are subversive actions. And I think it's kind of interesting to think about, you know, personally my role as a student and my role as an individual trying to resist the very thing that I'm being inculcated to do.

Guthrie Ramsey: Reproduce.

Audience member: Yes.

A.D. Carson: Yeah. Well, it's real. I'm glad you were paying attention in class.

Njelle Hamilton: Got time for one more question.

A.D. Carson: Warms my heart.

[laughter]

Deborah McDowell: I'm trying to figure out how I'm gonna ask this question, you know? It comes from a point you were making and it had to do with understanding what the listener's expectations might be and that you don't want to fulfill those expectations. That you know what they are. So, there are these conventions or these sonic conventions that you don't want to satisfy, so again, without suggesting that you go to music or literature or any other art form as if it's like a medicine cabinet, what are you, do you see yourself as re-educating the listener? Are you attempting in that process to make some comment on how people listen? That's the best way I can ask this question.

A.D. Carson: Yeah, I think that part of it is that, like, I realized how I've been tricked into, like how I've been lured—

Deborah McDowell: Uh-huh.

A.D. Carson: ...into listening more attentively.

Deborah McDowell: Uh-huh.

A.D. Carson: And then it's like a tool.

Deborah McDowell: Uh-huh.

A.D. Carson: Like if I wanna bring folks along, there's a way that, I think that there's a way that you kind of lay out the track and then folks like, you know, they see the tracks before them and, like, then they can close their eyes and they know they'll end up there. Or they feel they'll end up there or I can give them that and then there's like there're these ways where they're being pulled along and perhaps the track gave them the false sense that was where they were going.

Deborah McDowell: So, are you, do you want to avert sleepwalking?

A.D. Carson: Well no, I think it's like it's to, maybe. Because I'm also like never, I don't think, I've never made the claim that I'm not myself the sleepwalker, you know. And I think that there's, you know, ample evidence within that text um, you know, the speaker, like they may also be asleep. So—

Deborah McDowell: Uh-huh, uh-huh, uh-huh. Ah... So, there is no Archimedean point, there's no point outside. That was the question you were making earlier.

A.D. Carson: Yeah.

Deborah McDowell: There's no place you can stay that's free of all of these—

A.D. Carson: Yeah. And so, when I'm writing, like, those expectations that exist it's like, to me, it's less interesting to fulfill them unless it is being fulfilled for a very specific point. And so, like "Kill Whitey" is the best example of that, is that it's fulfilling these expectations in sort of a way that is, to me kind of funny, but probably not as funny to anybody else [laughter] because it's like, I mean, it's really to say, "I'm going to do it now. Like these are the terms on which I'm going to give you that fulfillment. So if you're going to sing the hook—I know there was a friend who was like, "So you, like I don't know what to say to you because I wanna play this song loudly in my car, [laughter] but if I do then I'll be playing this song loudly in my car and then people are going to wonder what's going on." And I'm like—

Deborah McDowell: ...so why would I play this song loudly in my car.

A.D. Carson: Yeah, and I'm like—

Deborah McDowell: ...since I can get shot for so doing.

A.D. Carson: Yes. And I'm like but it thumps hard enough that maybe people aren't listening. Maybe people aren't listening to the hook, they don't hear the words. If they do, then yeah, you've got some explaining to do, but that's between you and them and not necessarily my thing, which is also awful because like somebody could literally get shot for that. I think, you know, it stops being a joke when we bring Jordan Davis into the picture.

Deborah McDowell: You're right. Exactly. Exactly.

A.D. Carson: And think about what the repercussions are for something like that. So, it's like, there's this absurdity to it all that like gets really, really, really serious in the midst of our laughing. So, to sort of be somewhere within that mess and know that, like, it seems merely aesthetic until we start to give these concrete examples of where, like, those aesthetics are a matter of life and death. You know, when you're interaction in the world.

Deborah McDowell: Yeah. Yeah. One small thing?

Njelle Hamilton: Small.

Deborah McDowell: Unless somebody else has, small, small. Well we were supposed to go 'til 7:30, but we don't have to.

[laughter]

But I wanted to take up from Lanice. I think I'm remembering the question, because— I don't wanna try to remember it because I want you to reproduce that delicious eloquent,

Guthrie Ramsey: That was 16 bars!

Deborah McDowell: That point, I just want you to make that point again because it is itself so musical. From that come from Audre Lorde, the violence not so much begetting violence, I don't.

Guthrie Ramsey: Black women as collateral damage of the liberation quest. Yeah.

Deborah McDowell: Yeah. Exactly. And then A.D.'s response was equally delicious, it was the thing and the antidote, the violence and the antidote—

Jack Hamilton: The poison and the antidote.

Deborah McDowell: The poison in the antidote, which is kind of, that's a form of definition of homeopathy, right?

That's what happens in homeopathic medicine, am I remembering this right? Somebody help me.

Guthrie Ramsey: It sounds like, to me, Grimm's Fairy Tales, where the apple was the gift and the poison.

Lanice Avery: It's building up a resilience to it. Without curing it, right? Certainly not restoring it. Certainly not getting your mind back, and has nothing to do with what it does to lots of folks who die with exposure.

Njelle Hamilton: ...to get to the antidote, the dosage, somebody has to test it so people might actually die in the process of making the antidote.

Lanice Avery: Yes, often do. Often Black folks.

Guthrie Ramsey: Often Black women.

Deborah McDowell: Yeah.

Lanice Avery: Historically always us. Often Black women, to be specific.

Deborah McDowell: And I was thinking of two things as you were speaking, you know, it's been going around the last month, this exchange from the seventies between Nikki Giovanni and James Baldwin.

Lanice Avery: James Baldw—yasssss.

Deborah McDowell: Like where she's basically giving him a version of the same. But then I also thought because, I see you're wearing Invisible Man and it's a book stack and all and it's not in Invisible Man that Ellison is saying this but it's in one of the essays in Shadow and Act where he's really trying to explain corporal punishment and the resilience to corporal punishment in Black communities, in other words, why people beat their children, you know?

Lanice Avery: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Deborah McDowell: And obviously, I mean, it's so theoretically sophisticated and intricate but as near as I can tell, it's like, I am beating you up to keep you from being, to keep you alive, you know? This is my version, corporal punishment is the way what was that?

Guthrie Ramsey: Whew, whew... It's great.

Deborah McDowell: Yeah, but it's Ellison explaining this thing. Do you remember that woman in Baltimore after the—and everybody is, you know, let's give this woman an Academy Award, she sees this child out here and just goes upside his head and so, you know, I'm on my high horse, what? We cannot be condoning this.

Njelle Hamilton: On TV. On TV. [laughter]

Deborah McDowell: All the while, I'm mindful of the fact that not only was I subjected to corporal punishment, but in the era you were told to go outside and bring me a switch.

Lanice Avery: Get a switch. You're a part of it, you bring it about yourself.

Deborah McDowell: Yeah. Yeah. So, it's this—

Guthrie Ramsey: Wow.

Deborah McDowell: Yeah. This violence to prevent violence which is completely wack, but he's basically, and his own articulation, he wants to see it as an expression of love, right? I gotta remember the essay.

Jack Hamilton: I think it's the "Richard Wright's Blues" essay. I think it's the end of the, yeah. Which is really amazing.

Deborah McDowell: Yes, that would've been it! Because I was writing about Richard Wright. Exactly, it is in "Richard Wright's Blues."

Guthrie Ramsey: Alright, Jack! [laughter]

Deborah McDowell: It's the one about corporal punishment as homeopathy and I don't know why I'm on this tangent but let me stop.

Lanice Avery: I mean, also though that you're saying, "Beat you up to save you," and A.D. said, "I don't wanna be up, I wanna be down." And so that's interesting to say, like, "Sure. And also, that's never the goal, we don't wanna survive oppression, like we don't wanna survive violence, we want to not be violated, period."

Deborah McDowell: Right.

Lanice Avery: So then how do we think about a strategy that has not to do with complicity or resilience to it to fine-tune our ability to withstand, like how is it to not engage it? Right? Even if it means killing Whitey, enacting a violence harder on you so that I'm not, like is that freedom? Can you even get free? We know you can't that way.

Deborah McDowell: Right.

Njelle Hamilton: So, kind of what you know I was joking that's like my favorite song, right? It's a legitimate banger, right? Then every line undercuts what you think the previous line meant, right? Like, so, one of my favorite lines is, "the soundtrack to end white supremacy," and like if we actually do the thing that the words do, which is end white supremacy, don't they also hopefully, ideally, right? That kind of dismantle the systems that kind of—

Lanice Avery: We know better.

Njelle Hamilton: Right, this is kind of exactly, right, that the system is dismantled, right—

Lanice Avery: Then you just take over the system and do the same thing again, if that was the way you wanted. You go to war to take them over then to enact war. Like occupation and dominance is the language, so you can't get it. You get it how you live [laughter] and you will never live another way if you only got it that way. And so—

Deborah McDowell: The violence is always generative.

Lanice Avery: Right, right, which is my question about Audre Lorde and thinking about the intrapersonal languages that we get, like what do we really adopt that engenders a possibility of freedom. Often it is not if that is the language and if we take it up without scrutiny.

Deborah McDowell: This really. [laughter] I, anybody else? Yeah, this is, see, this is what, A.D.

[applause]

◆◆◆

11. Epilogue

"So there you have all of it that's important."

...I'm appreciative to all the participants in the roundtable for what I found to be a very productive conversation. I'm deeply indebted to Dr. McDowell for her efforts to bring all the voices present into the conversation that took place, and for her work helping to organize the event that took place. It's difficult to convey my gratitude to the participants for taking the time and the energy to do this. To come together to listen and discuss and challenge and ask questions, especially in the context that this took place, was incredibly helpful for me to think through my work and what I might do next. I think particularly about Dr. Avery's questions about proximal violence and the kinds of instructions we might give the next generation for the tools we put in their hands and Dr. McDowell's reiteration of those questions in the Q & A and how I might carry them over into future projects and my current teaching. I wonder if an answer to Dr. Avery's questions can be worked out within this form. I'm certain that in the classroom space, where collaboration is essential to the process and the project, and the students don't have much choice about who they work with, there's a kind of built-in challenge to one perspective or one identity taking over, and the result is usually a shared perspective represented throughout the project. This should be a lesson to me about my habits of collaboration if my intent is to represent something outside of my own perspective, which wasn't what I was attempting to do on this or any other project, but it's important to consider, regardless.

Still considering the challenge of change or transformation re-presented from the Black Perspectives interview in the prologue, I wondered if there might be similar questions about the follow-up to Sleepwalking 2, titled i used to love to dream and released with University of Michigan Press. Rather than a listening session and discussion after publication, i used to love to dream was submitted for peer review and was the first rap album to go through that process for publication with an academic press. I submitted the finished project unmastered in case changes were suggested. There was feedback on the lyrical content, but no changes suggested. Most of what came out of the process were ideas about how the project would be hosted in their online platform and what kinds of materials would be included with it. Rather than an explanatory essay that I feared might take away from what the album says, we agreed on a documentary film on the making of the album, talking with me, the producers, the sound engineer, and my brother and my mother. There are also two essays that are related to the album, but they don't attempt to explain the content.

It should be noted, in case I don't say it anywhere else, that track seven from i used to love to dream, ""ready," was written and recorded the night of the roundtable, after we'd done the listening and conversation, after we had dinner, and Truth and I were in the car he suggested we go back to the lab and make some music like we did when we were undergraduates. The song does a great job of describing the day and the journey, the process that led to the roundtable, and the outcome.

Further reading on Sleepwalking: Kajikawa, Loren. (2021). Leaders of the new school? Music departments, hip-hop, and the challenge of significant difference. Twentieth-Century Music, 18(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478572220000262

◆◆◆

12. References

Baldwin, James, & Giovanni, Nikki. (1971). A conversation [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Jc54RvDUZU

Carson, A.D. Words and stuff by A.D. Carson [Personal website]. Retrieved from http://phd.aydeethegreat.com

Ellison, Ralph. (1952). Invisible man. Random House.