This Inventio webtext is an experimentation to pursue pluralities by exploring how text, video, and images can be braided to evoke sovereign relationships. Indigenous sovereignty is a significant premise of this work, animated through weaving and yarning. Weaving and yarning is both a practice of Indigenous sovereignty and a graceful methodology that invites non-Indigenous and Indigenous sovereignties to strengthen and maintain sovereign relationships. The selection of videos, images, and quotes from several Wiradjuri-led gatherings are diffuse tracings of our collaboration that elicits many hands, bodies, materials, rhythms, atmospheres, and landscapes that also participate in sovereign relationships. The composition here is poly-vocal, multi-dimensional, and phenomenological to experiment with the affordances of this digital journal, in an attempt to move away from linear, functional, and analytical reporting favoured in design and technology. In doing so, we grapple with ethical, political, and epistemological challenges in these disciplines to explore inter-epistemic, inter-cultural, inter-ontological ways to share our work and methodology, and in turn, demonstrating ways we are attending to sovereign relationships that underpin our collaboration. All together, we invite a sensual connection in the readers' imagination as an encounter somewhere "in-between" to kindle the richness of sovereign relationships.

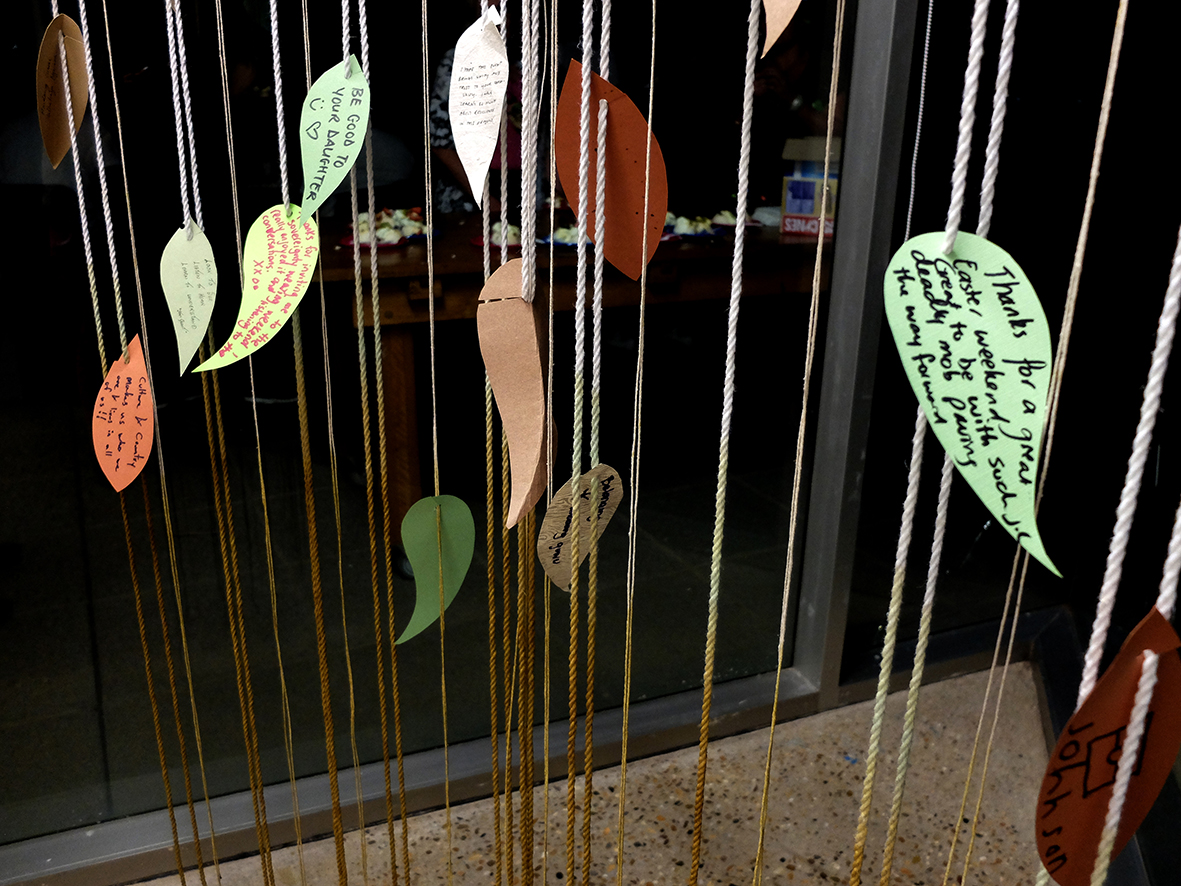

Readers are invited to re-size their screens and move some of the images and texts around to participate in weaving their engagements with this webtext. Permission to share images online has been granted from Wiradjuri Elder, Aunty Lorraine Tye, who led a Dabaamalang Waybarra Miya (Sovereign Weaving) event where videos and photographs were taken. Permission was also granted by those who appear here. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander visitors are advised that this website contains images of people who have died.

Pluriversal design

This webtext is accessed by readers using powerful technologies and information architectures designed within knowledge systems that value openness, accessibility, uniformity, and universality (Withey, 2015). This orientation to research dominates in design and technology. Many scholars in these disciplines have argued for the need to interrogate such objects and systems through a sensitivity to asymmetries in culture, power, history, politics, knowledge, and practices in all their complexity and diversity (Philip, Irani & Dourish, 2012) so that dominant worldviews, values, and literacies does not become hardwired in the objects, systems, environments as design (Winschiers-Theophilus, Bidwell & Blake, 2012). This is acute for the non-Indigenous art, design, and media co-authors of the webtext, to pursue their work with care and carefulness, in collaborating with Wiradjuri artists and scholars in law, health, and Indigenous education (also co-authors), and more broadly with Wiradjuri nation members in Australia. To pursue this work, we have taken pluralities of thoughts, knowledges, practices, and ways of being and becoming as the premise of our research. We follow Arturo Escobar's (2018) argument for "pluriversal design" for an inter-epistemic, inter-cultural, inter-ontological recognition to acknowledge multiple linages and mutual care to examine the location of our own geo-politics and explore how to act, know, make, be, and become together.

Re-framing sovereignty

We discuss how collaboration among Wiradjuri and non-Indigenous co-authors was undertaken by attending to our consciousness of sovereign relationships. Using the term "sovereignty" follows prominent Aboriginal and Indigenous scholars to reframe it from its colonial usage towards positioning the geo-politics of our work in Australia where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are sovereign nations with distinct language, laws, culture, knowledge, and governing systems. When an Indigenous sovereign offers an invitation to a non-Indigenous person to share place and knowledges, this obliges a non-Indigenous person to continually attend to the condition of this relationship (West & Vaughan, 2017). This is called a lawful relationship (Behrendt, 2003) that can only exist through respecting the sovereign activities of Indigenous peoples—by acting sovereign with them and alongside them, not on behalf of them. In other words, continual effort to examining our own relationships to Indigenous sovereignty becomes the premise of sovereign relationships.

Celebrating Wiradjuri sovereignty

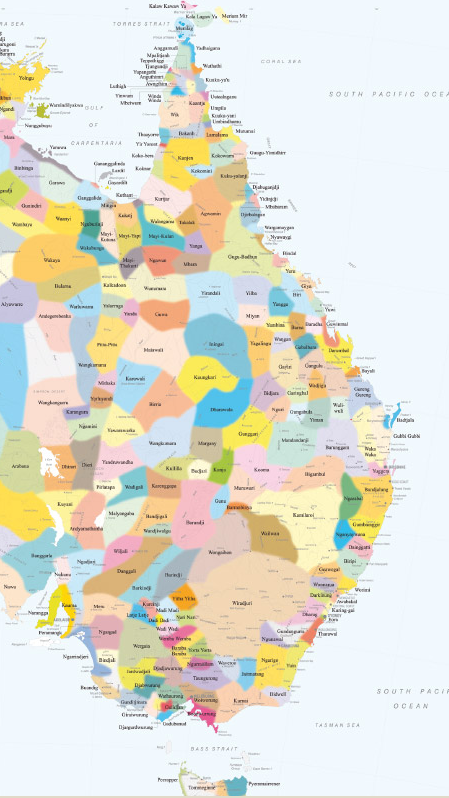

Wiradjuri Nation has one of the largest territories on the Australian eastern seaboard in central New South Wales. It is the "land of the three rivers"—Wambool (Macquarie), Kalare (Lachlan), and Murrumbidgee or Murrumbidjeri—that contour their Country. Country is much more than the land, having greater significance that connects to ancestry, culture, identity, and spirituality, and therefore sovereignty (Moreton-Robinson, 2000). We have collaborated over many years to mobilize events that celebrate Wiradjuri sovereignty, and we draw upon one of the major gatherings, Dabaamalang Waybarra Miya.

Weaving and Yarning

Weaving and yarning are significant sovereign practices shared by many Indigenous peoples and nations. Yarning is widely acknowledged as a process of "making meaning, communicating, and passing on history and knowledge" and also as a way of building relationships based on trust and honesty (Bessarab & Ng'andu, 2010, p. 38). Yarning can also achieve deep equity, according to a prominent Wiradjuri design scholar, Norman W. Sheehan (2011): "Deep equity is the inclusion of all identities, features, and factors because they are assumed to be equally aware, alive, and capable of voicing their concerns" (p. 70). Yarning circles can provide an equal sharing space "that enriches the creative potential of a group because, as the speaking role moves, individual statements become more spontaneous, merging and connecting to become an emergent and creative conversation between minds" (p. 70).

A confluence and welcoming of many

Exploring ways to evoke weaving and yarning sovereign relationships is a key contribution of this Inventio webtext. The pursuit to explore what Escobar (2018) called inter-epistemic, inter-cultural, inter-ontological ways of narrating our personal stories of sovereignty and sovereign relationships has led us to compose multimodal and poly-vocal ways to highlight how these practices are enacted, participated in, and welcome many to further enfold and nurture sovereign relationships. Such entwining of non-textual elements demonstrates plurality of engagements and materials created by, with, through many gestures, places and movements. These materials are important and plentiful sites to story-tell intersections, coexistence and correspondences, bringing people together, creating shared experiences and providing opportunities to connect as nation members. Memorable moments during Sovereign Weaving were often just being together—sitting on the banks of the Murrumbidgee river and listening to squawks of cockatoos at dusk, or watching the artists manifest beauty through weaving reeds and native bird feathers. These are powerful co-ontological enactments of sovereign relationships. We have aimed to make the plural human and non-human participation in sovereign relationships evident through this Inventio webtext to imbue intimate and intangible facets of being that have been just as significant in shaping the gatherings.

Sovereign relationships by Linda Elliott

We learn from Linda that her sovereignty is premised upon acknowledging her citizenship on Wiradjuri Country and then enacting this awareness through learning Wiradjuri language and key concepts of significance to the Wiradjuri. We also hear how weaving and yarning allow ways for her to learn about important Wiradjuri concepts, and the invitation to join a weaving circle is an acceptance of who she is. The notion of "we" is significant for Linda when describing her sovereign relationship, resonating with the notion of co-ontology where the "We" precedes the "I" and already being-with-many (Nancy, 2000). This "we" for Linda includes her on-going connection to Wiradjuri Country and community. We also hear about her openness for learning and listening to the Elders as a demonstration of a reflexive, responsible commitment to a sovereign relationship, to overcome fears and paralysis of making mistakes and to strengthen mutual aims.

Sovereign relationships by Aunty Lorraine

We learn from Aunty Lorraine that yarning and weaving are inter-twined as part and parcel of Wiradjuri sovereign practice. Through yarning and weaving, stories, knowledge, inter-generational relationships continue. We also note that yarning and weaving welcomes everyone's stories. This is a particular feature of the Hands On Weavers Inc., which Aunty Lorraine and Linda are part of, as an example of reconciliation in practice where "all are welcome no matter what your heritage" (Tye, Elliott, & Clancy, 2017).

Sovereign relationships by Yoko Akama

We learn from Yoko that her sovereign relationship is a way to connect through her Japanese cultural practices of respecting thresholds when invited and introduced, which also attunes her to sites and moments where this is not welcome. So when she is taught to weave by a Wiradjuri Elder, she sees this as another invitation to be in a sovereign relationship. Participating in Wiradjuri practices of sovereignty, she is bodily, materially, and perhaps even spiritually connected through her Japanese sovereignty and ancestry, rather than to know or understand Wiradjuri sovereignty. For Yoko, the notion of "with" as a pre-stated condition is a compelling dimension of sovereign relationships, where each person's sovereignty is acknowledged, welcomed, and becomes part of an on-going co-ontology.