Windhoek

Conference exhibition

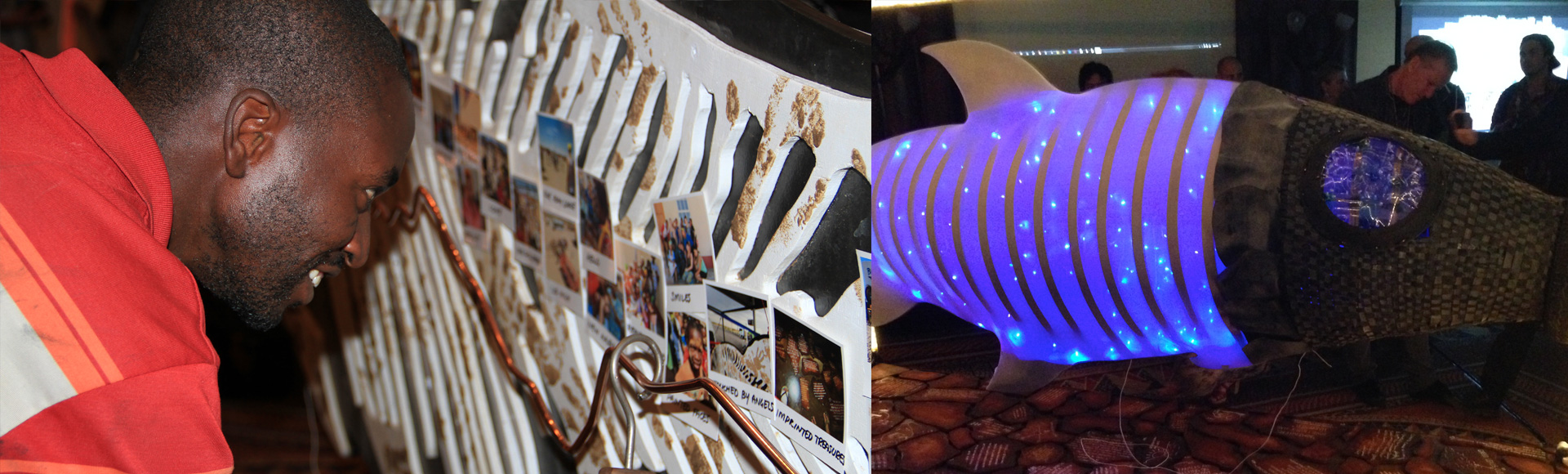

Located in the geographical center of Namibia, this cosmopolitan city is also at the center of economic, political, cultural, and social activity in the country, and it was the setting for the 13th International Participatory Design conference. For each of the 36 participants on the journey, it was apparent that the destination held widely varying expectations. For some it was a reminder of an earlier time in history, of the South African occupation during the border war before Namibia’s independence, and for one student, it was home. With feelings put aside, a frenzied hive of activity ensued in anticipation of the tight deadline of one day in which the project team had to prepare the fish for the opening event.

At first, general chaos characterized our arrival as we realized that the resources we needed to complete the installation were not to be found close at hand and that the sprawling expanse of the conference center provided a challenging scenario in which to do the exacting work according to plan. The reality of carrying the very large, unfinished Tigerfish into the conference center grounds soon prompted a sense of urgency in bringing about the final transformation from story gatherer to interactive exhibition piece. Some very creative solutions to the challenges presented brought about some surprisingly appropriate design decisions, along with surprises as to which of the students took leadership roles.

Participation

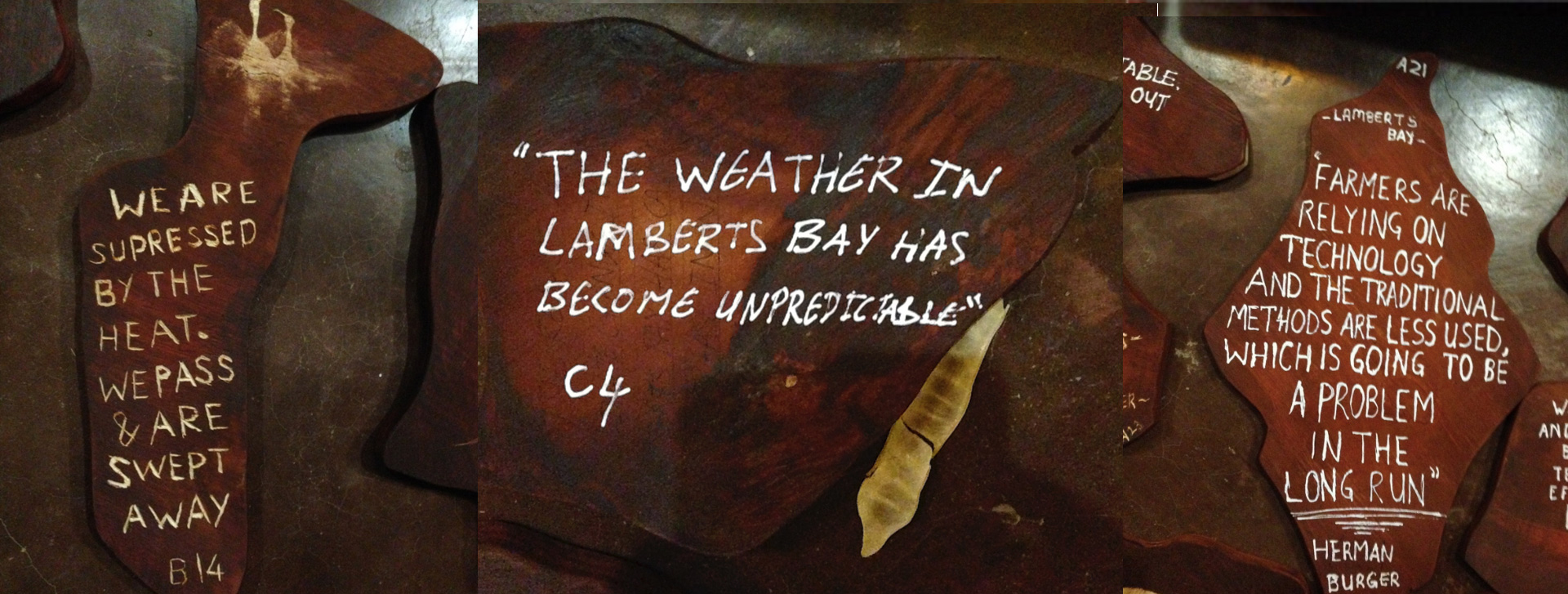

The first decision, in terms of the integrity of Fiscilla’s mandate as a participatory designed artifact, was that stories gathered by each student and inscribed on the cracked earth tiles underneath the suspended fish had to be put carefully in place, according to the pre-determined pattern envisaged back in the studio. A team set to work, while others dedicated most of the day to attending to the aesthetics and electronics needed to bring Fiscilla to life.

The integrity of the hand prints made by the Noordoewer children had been lost in the unexpected rain on the long road to Windhoek, and it was decided unanimously to re-apply the mud prints. So much had gone into the physical design and construction of the installation, but what still remained was to tell Fiscilla’s story in the form of an opening performance and unveiling due to happen at 7pm the same evening.

Responsibility for this fell to Khanya, who had shown her growing commitment to the project and displayed a strong will toward keeping the essence of climate change and sustainability at the fore. She was encouraged to lead the way toward a fitting tribute in the form of a poem, with the surface design students responsible for construction of a seawater colored veil with which to reveal the message-carrying installation to the conference audience.

Discussion

Connecting

In the preparations, Hafizah described the frantic activity: “Yes you felt it, when you stood and watched everyone’s enthusiasm…we’re in this to win it! If something goes wrong were going to find another way to fix it. That’s what I got. And every spot, every place that we went it just grew stronger towards the end—right, we going to make this work, no turning around.”

Stehan remarked on the final preparation that when “we had to do some repair work, we realized that there was something missing, the hand prints had been washed away by the rain and we realized we had to bring back the hands, but we don’t have the kids here, we have to be the kids almost. So we re-enacted what happened on that day and so in that moment it was kind of like doing it again almost ceremonially, our hands our fingerprints are now part of this…a kind of a sign that we were here, proof—I don’t know, there was something there, I can’t quite put my finger on it.” The re-enactment proved yet another performative process for the students as they gathered together what had come out of the hinge moments for them on the journey. They remembered these moments with some emotion, even describing the incident with the children's hand prints as moving them to tears and the link to the ceremonial act of reinstating them.

“I think what made this trip so interesting, apart from it being outside the traditional setting was the fact that we weren’t actually being told what to do, all you guys did was present us with real life challenges that we had to solve and through that not only did we utilize the skills that we were taught, but [we] also then found new skills like the weaving, who knew that I could weave like that? Never done it before, but presented with that challenge, solved that problem and I think that’s one of the best things about changing settings for learning and creating different facilitation processes is that you get surprised by yourself”. Here Khanya displayed her ability to connect appropriate skills and knowledge in the moment that it was required in order to move productively forward.

An awareness of finite resources had been a reality throughout the journey, as Khanya summarized it: “We had to come up with something…we just thought, how are we going to do this? How’s this thing going to sit? You yourself are the only resource…you’ve got to sort of make do with what’s in front of you, you can’t leave, you can’t turn away. But what was remarkable was how much creativity came from that, you know, just on the fly…we have a problem, how do we fix the problem…I think that for me was one of the key things on that trip”.

Performing the learning experience

“Its abundance is endless

this place I call home

I swim far up field, up rivers and streams

my scales are brilliant, crisp, look at how they gleam

my belly is empty, barren with decay, perhaps I’ll disappear and wither away

I dream of the rivers where I can swim away

blow the horns, Ubuntu, my people, let us unite

we have the capital to combat this plight

new perceptions, new motives, the possibilities run wild

let us free our minds our eyes un-blind

participate, communicate, let us drive

the man and the fish-let us leave none behind”

Khanya’s tribute performed during the unveiling of Fiscilla performatively moved both the project experience into a new phase, as well as the audience—to much applause. From that moment on Fiscilla became an interactive art piece that drew an audience and engaged them with stories and play to convey her message of resource scarcity and a plea for active involvement in matters of climate change.

On the night of the opening, our dean, who had been a participant on the journey, introduced Fiscilla with these words: “We read stories, we shared stories, we listened to stories, and it bound us together, and we would like to share with you the stories that are written below, the story that is on the fish.” He also remarked later that, based on his vision for the design faculty, he found it interesting to see how disciplinary silos were broken down, and how that process played to everyone’s strengths, enhancing individual responsibility and positive interdependence.

This broad comment reveals the many layers of collaborative activity that had unfolded, and the dispositions that had surfaced of transdisciplinarity, sense of identity, and individual agency along with networked agency. The participatory presence of senior management on the journey was significant in the way that it allowed a window into how the design process unfolded through multiple iterations within the group and its interactions with community along the way.

Conference goers commented positively on the interactive exhibit with one saying, “I actually saw this fish being built outside—I come from Zambia and so I know the importance of fish within our local environment,” and another, “It attracts you firstly and then draws you in, and as you move you can connect with the stories, it moves you.”

The senior project leader, Alettia Chisin, remarked on her appreciation of the opportunity to connect with others, “If you are at work and you are rushed you don’t have a moment to feel that in between space, that quiet space, that liminal space that exists between people, there’s almost a pause between notes that is very sensitive and we are usually so rushed that you can’t quite fathom and step into that and be with that person, and that happened in a big way on the trip.”

Reflection

Expressive learning

In Windhoek, the performative aspects of this project became the driving force as the group prepared for the opening event, and students’ various roles that had been emergent during the journey north now crystalised into concerted action as everyone drew together to deliver on deadline. The learning experiences along the way had brought about a strong sense of ownership and pride in the group, and the desire to do justice to this was palpable in the last hours of the build. The participatory practice of the community had evolved a culture within the travelling group; this had happened over time through many improvised performative events where meaning became more complete for the group as it was intelligibly communicated and expressed to others. The asynchronous nature of these multiple expressive events, in many places along the way, produced learning and developed dispositions in students that were uniquely productive as they emerged out of trust in the process, a “laying down a path in the walking” (Varela et al., 1993, p. 237).

An eventful space

What emerges here is how the nomadic disruptions, transgressions, and expansions of the learning space had created an eventful space where, what was initially disconcerting had become everyday in the journey experience. These spaces provided opportunities for students to exercise and discover latent abilities, and multiple social, material, and processual skills. Enabling these skills to be exercised in a dynamically enacted and applied way is what evoked a dispositional awareness and orientation toward learning and working in resilient and adaptive ways. A broader range of knowledge processes being exercised revealed the micro dynamics of a pedagogy of multiliteracies where powerful learning had begun to arise from weaving between experiencing, conceptualizing, analyzing, and applying in an explicit and purposeful way (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009).

In traveling with students in this manner, we as educators and researchers had been equally affected by the threshold crossings, the personal and pedagogical boundaries that had been transversally re-negotiated during the events on the way. This active engagement by staff with students as they learned produced a mutually constituted world within the traveling community, where intense bouts of action were balanced with reflective phases in between as we journeyed through the contested place-based environments and spaces for self-realization. These liminal and temporal spaces allowed for stronger connections to be made, both among staff and between students and staff as we negotiated the tensions, tedium, successes, and unexpected pleasures of the journey.