The mic stand used by poets at the TYPS 2013 Championship in Tucson, Arizona

photo by Adela C. Licona

The multimodal productions at the heart of this webtext—the slam poems performed, recorded, and circulated via social media by TYPS participants—offer not only a wealth of insights into the force and function of slam poetry in specifically youth-oriented contexts, but also the opportunity to recognize creative, playful, activist strategies deployed by youth as they engage with the complexities of race, class, gender, sex/uality, and citizenship that produce and are produced by state crises such as those emerging in Arizona. We understand multimodality as “a complex rhetorical performance for producing bodies and spaces through multisensory expression—performances composed through and with consideration of audience engagement and the relational playOur deliberate engagement with the concept of PLAY in our work is a demonstration of the resistance we practice at the Crossroads Collaborative to the imagined and rigidly imposed divisions of an adult–youth binary. In other words, we take play seriously. Our working definition of play is informed by Ken S. McAllister’s (2004) Game Work: Language, Power, and Computer Game Culture, in which McAllister demonstrates the ubiquity of play as a term and a practice describing our social and cultural activities and productions. Following Londie T. Martin (2013) in The Spatiality of Queer Youth Activism: Sexuality and the Performance of Relational Literacies through Multimodal Play, we understand play as a rhetorically significant and often relational mode of critical and creative meaning making. When understood and approached as serious work, as we believe it should be, play can illuminate both the joyful and the unjust. of senses” (Martin, 2013, p. 126). As an interdisciplinary collective, we are also called to consider the relational play of historically juxtaposed inquiries and methods; in this webtext, we have brought together academic inquiry and slam poetry performances, quantitative and qualitative coding of themes that emerged through these inquiries and performances, and participatory action research practices to bolster interdisciplinary research in rhetorical practices.

To illustrate, two initial projects helped us better determine ways to generate reciprocal exchanges with TYPS poets. First, we set out to discover to what extent the substance of TYPS poetry and performances could engage with and inform the issues that drive the Crossroads Collaborative. Together and separately we read, listened to, and analyzed 28 TYPS poems that were randomly selected during the months of March and April of 2011. During this time period, TYPS was completing its first season; the first championship took place in April 2011.

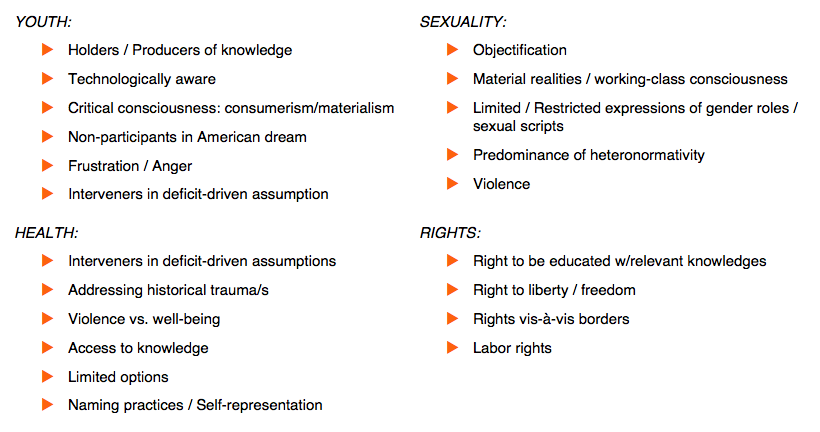

Poems were analyzed through a cross-disciplinary coding process initially based on the broad themes of youth, sexuality, health, and rights that frame the work of the Collaborative. Researchers then created sub-themes partly inspired by asset-drivenASSET-DRIVEN discourses and practices are rooted in the belief in the strength and value of all human beings. This approach is committed to recuperating and teaching the value and potential of lived individual, home, and community knowledges, particularly including culturally relevant knowledges. González, Moll, and Amanti’s (2005) concept of funds of knowledge can inform such an approach., feminist, queer, participatory, and rhetorical methodologies (see “Themes”). These qualitative methods oriented us first to look for and identify individual and community strengths. We used these methodological frameworks to also identify creative world-making practices and non-normative expressions of subjectivity, counter-stories, coalitional practices, and liberatory practices for social justice. Finally, these methodologies called us to pay particular attention to the persuasive potential in slam poetry texts, performances, and contexts. Researchers used these methodological frameworks to closely read and then code poems based on these themes and subthemes.

Parallel to this rhetorical, qualitative coding, for quantitative coding and analyses, we selected poems randomly rather than based on their content: this method draws from probability theory (Rudas, 2004). Each poem would have equal chance of being selected for coding, and thus the resulting codes and themes would most likely represent the themes present through the full collection of poems. Two coders read each selected poem for pre-determined YSHR themes (present versus absent). Coders then met for discussion and to identify any discrepancies in the coding process, which were resolved by consensus. This content analysis method was used to quantify categories and create a “numerical based summary of a chosen message set” (Neuendorf, 2002, p. 14). Once coded, the numerical dataset could be analyzed through frequencies (number of thematic codes present across the collection of poems) and statistical tests for whether themes present across the poems are related: Are some themes more likely to appear in the presence of other themes, or are all themes equally likely to be present without regard to others? The use of both qualitative and quantitative coding allowed us to consider the nature and frequency of themes emerging in our analyses, which gave us a sense of the needs, dreams, desires, and concerns that are most urgent to local youth at this particular time and in this particular context.

Second, as part of a project to organize videos uploaded to the TYPS YouTube site, TYPS youth and members of the collaborative tracked themes in TYPS from all of the poems posted online between January and December 2011. In identifying themes for the purpose of “tagging” each video, thus making it searchable online, we found a significant emphasis on social justice issues, such as immigration, race and racism, and gender and sexuality; a desire to express cultural identifications; and evidence of the conflicts and clarifications that accompany self-identifications. Resistance becomes a collaborative effort for those youth who wish to slam about their experiences and their concerns, and the audience—while including adults, from parents to interested community members—mostly consists of youth who are poets themselves and/or are there specifically to support the poets and the endeavor.

What we have discovered connects with Dolores Delgado Bernal’s (2002) focus on the agencyThose interested in understanding the discourses of and capacities for social change, how it is produced (enabled and constrained), under what conditions, who animates it, and to what end/s, often find themselves grappling with the concept of AGENCY. At the Crossroads Collaborative, we begin with Radha S. Hegde’s (1998) reference to agency as “the coming together of subjectivity and the potential for action” (p. 288). We then draw significantly from Carl G. Herndl and Adela C. Licona’s (2007) understanding of agency as a “diffuse and shifting social location in time and space, into and out of which rhetors [read: social actors] move uncertainly” (p. 133). Like Herndl and Licona, we, too, are interested in the opportunities, as well as the constraints, for those engaged in change-making discourses, practices, and relationships. We extend this interest with a focus on how such change-making relates to youth, sexuality, health, and rights. We find Herndl and Licona’s concepts of constrained agency and agent function, as well as their considerations of the relationship between authority and agency, particularly useful to our work as we, too, understand the possibility for social action to be sometimes but not always reproducible across social contexts, practices, and relations, and neither entirely determined by structures nor entirely bound by the neoliberal illusion of a fully autonomous individual. of youth in questioning, developing, generating, and gaining knowledges. Delgado Bernal's work on youth agency focuses on formal educational settings, and, while our research recognizes the complexities of formal and informal educational contexts, it does not enforce a strict division between formal and informal educational experiences in terms of the deficit-drivenDEFICIT-DRIVEN discourses and understandings of non-dominant others have been reproduced across disciplines and community contexts. Such understandings are rooted in dominant, and often stereotypical, assumptions about knowledge, learning, desire, behavior, and aptitude. They are negatively framed through stigmatizing and even pathologizing discourses of risk that ignore the place and potential of social and cultural capital, particularly in and from non-dominant contexts, as well as the force and function of structural inequalities. Academics and activists interested in disrupting deficit-driven discourse look to funds of knowledge that can point to an altogether different perspective and line of inquiry based first in asset-driven understandings of difference and of marginal and marginalized communities. perspectives that emerge when adults organize educational contexts for youth.

Again, the legislative context in Arizona helps create a framework for understanding agency in relation to the identified themes. For instance, a critical examination of AZ SB 1070 (Arizona's anti-immigration bill, commonly referred to as the "papers please" law) conjures common themes associated with immigrants’ rights, such as the ideology of the “American Dream.” We identified “American Dream” as a theme to consider during the coding process. We generated themes that we believed would help us listen to the connections among youth productions as they responded to the restrictions in place through the Arizona legislature. Because of our grounding in LatCritLatina/Latino Critical Theory, LATCRIT, arose from CRT and critical legal studies with an emphasis on the implications of racial and racialized, as well as other structural inequalities, for Latin@s across contexts with a particular emphasis on legal and educational contexts. It serves as a theoretical intervention to the erasures of Latinidad that are affected by Black/White binaries and therefore contributes to a more complicated understanding of race and racialization., we also wanted to know to what extent youth felt a capacity to intervene, through poetry, in deficit-driven assumptions. We also looked for an awareness of historical traumas and the prevalence of acts of violence, as well as any discussion about limited options and the desire for certain kinds of knowledges and resources about health and sexual awareness. We wondered to what extent types of sexual education would play a role in how youth choose to speak up (or not) about sexuality, reflecting about how normative and heteronormative scripts perpetuate specific views about sex, sexual orientation, and minoritized statuses. Finally, we looked for youth interpretations of individual and collective rights, in particular through the lenses of education, as well as concepts of liberty, borders, and labor.

Background images in this section from mural and grafitti photographs by Steev Hise.

Table of themes identified across the poems analyzed in this study

After the researchers coded the 28 poems, they recorded specific information about multiple themes that were present. The theme of youth was the most common in the poetry and included several prominent sub-themes. Analyses revealed that the most common sub-theme present throughout the poems was the development of individual youth identities: one third of the poems included this theme. The research team conceptualized this theme as a proclamation of self, where youth expressed who they are through the use of specific identity terminology; other youth discussed feelings of being lost, confused, or unsure of self. For example, this line from an April 2011 poem challenges popular notions of masculinity: “If the letter ‘M’ on my ID is the first thing to define me, then why don’t I feel like a man?”

The second most common theme expressed in the poems regarded youth as holders or producers of knowledgesWe deploy the term KNOWLEDGES rather than “knowledge” to be explicit about the different—sometimes competing, sometimes complementary—knowledges that circulate in the communities in which we are engaged. These range from academic knowledges across disciplinary boundaries, to youth knowledges, to broader community knowledges. Recognizing that different knowledge systems are at play in and from distinct locations, we can also recognize that such knowledges are valid and can inform our research. When we position ourselves as learners who can be informed by the lived knowledges guiding everyday decisions, we open ourselves to deeper understandings of youth practices, interests, needs, strengths, dreams, and desires. In the Crossroads Collaborative, we also work to ensure that differing knowledges are translated, so that those of us involved in local collaborations are legible to one another as collaborators who share interests around youth, sexuality, health, and rights.. Our team conceptualized this theme as expressions by youth that they were capable of interpreting and understanding things around them, and of making their own decisions based on their knowledge. In addition, youth described intervening in deficit-drivenDEFICIT-DRIVEN discourses and understandings of non-dominant others have been reproduced across disciplines and community contexts. Such understandings are rooted in dominant, and often stereotypical, assumptions about knowledge, learning, desire, behavior, and aptitude. They are negatively framed through stigmatizing and even pathologizing discourses of risk that ignore the place and potential of social and cultural capital, particularly in and from non-dominant contexts, as well as the force and function of structural inequalities. Academics and activists interested in disrupting deficit-driven discourse look to funds of knowledge that can point to an altogether different perspective and line of inquiry based first in asset-driven understandings of difference and of marginal and marginalized communities. assumptions. For example, the line “I am textbooks of a single history with a misguided interpretation and only one side to the story” challenges the limitations of educational settings. In this way, TYPS performances reflect slam poets’ desires to actively intervene in deficit-driven discourses that too often criminalize and pathologize youth and their home communities. Slam poets are evidently aware of the limiting effects of such discourses and often slam in resistance to them. They insist on speaking their needs and on asserting meaningful self-identifications.

Many of the poems discussed rights: 15% of youth talked about the right to be educated, 21% talked about the right to certain freedoms or the possession of certain liberties for the poet or others, and 18% discussed the right to be heard and respected as poets. Only one poem discussed labor rights, and two mentioned border rights: These latter poems described what it means to be a citizen within marked territories, and youth perspectives on immigration and border-based violence.

Fewer of the poems included themes of health or sexuality. Less than 10% of the poems included discussions of addiction, limited or restricted expression of gender, predominance of heteronormativity, relational or sexual violence, limited options to health care, and knowledge about health. Although these health and sexuality themes were uncommon, the poems often focused on emotions, relationships, and love.

Alexia Vazquez focuses on themes of immigration and identity. She uses numerous tropes related to growth, evolution, progress, nature, individuality and individual achievement, bullying, sexualized/gendered pejorative phrases, nostalgia for traditional family roles, nostalgia/longing for and criticism of particularly classed child developments, work without labor, dreams of capitalist middle class success, dreams of humanization, and a multicultural and multilingual identity as an asset. She provides a chronicle of key moments in her childhood that reflect movement, marginalization, and connect with a plant metaphor that meditates on roots and rootlessness. Her tone and delivery are important in that she demonstrates the complicated mixture of emotions that accompanies details associated with both oppression and opportunity. In the latter portion of the poem, she speaks quite clearly to an audience that is the majority. The poem reflects a desire to invert hierarchy—to look for a place in the conversation and recant injustices. She uses asset-drivenASSET-DRIVEN discourses and practices are rooted in the belief in the strength and value of all human beings. This approach is committed to recuperating and teaching the value and potential of lived individual, home, and community knowledges, particularly including culturally relevant knowledges. González, Moll, and Amanti’s (2005) concept of funds of knowledge can inform such an approach. descriptors, reconfigures displacements, and defiantly announces that she is staying.

Vazquez’s poem is timely. In the midst of daily deportations, desert crossing deaths, and immigration debates, her poem tells the story of thousands. And, despite the injustice and oppression Vazquez has felt, she has not been silenced. Politicians in Arizona seem fearful of youth uprisings, but the harsh and irrational measures they take to silence youth (especially Latin@ youth) appear to fuel an even greater commitment to justice and equality for many youth. Poems and stories like Vazquez’s warrant attention from anti-immigration proponents. Unfortunately, adults do not tend to view such texts as having authority. Vazquez challenges conventional and academic knowledges. Her poem reflects a wisdom that would challenge the ways in which Latin@s, women, and youth are too often regarded in this country. She calls out what is unnatural about the world by saying, “Because when 65,000 dreams are denied a year, there is something wrong.” These are numbers the poet has integrated into her work that are not cited but can be understood to represent both the imagined dreams and lived stories of undocumented people in the U.S. Perhaps she uses this number to shock the audience as well as to exude her experience, understanding, authority, and truth about a lived reality, bringing together stories and numbers to emphasize outrage.

Enrique Garcia’s poem is another example of the importance of youth knowledges in regressive political contexts. The poem reflects a focus in perspective on the influences, obstacles, and opportunities for Latin@ youth in Arizona. Like other TYPS poets, he takes up the subject of money and materialism (e.g., the repetition of brand names—Chucks, Jordans, Vans). The tone toward politicians and adults who falsely claim to understand struggles is one of anger; this too connects with many of the poems that are speaking in anger and frustration to un/named figures of authority. Through both the invocation of brand names (in this case, shoes) and the mention of the capital of sex (e.g., “living in a culture of man, get that pussy”), Garcia alludes to a keen awareness of political economy and the stratified nature of capitalist and materialist culture as it is characterized in the US. He invokes competition and racial tension regarding dating through the metaphor of Libby (Lady Liberty) dumping the addressed audience for Uncle Sam’s nephew, Matt, materialism. Garcia’s poem is geographically expansive and alludes to several locations where social injustice has occurred. U.S. culture and food are used as a metaphor for the overabundance, corruption, and political red herrings used to distract the addressed audience from a more complicated reality. Garcia also explicitly focuses on rights through abstract references to capitalism, exploitation, and poverty on the Mexican/U.S. border and in Africa.

In one TYPS performance, a group poem emerged, showing youth coming together to express both collective and differentiated feelings about place. Here, poets were performing for an audience but listening to each other—poets from different backgrounds but with a similar investment in place (South Tucson). It is an example of the capacity to listen, to question cultural logics, to consider where and how the circumstances being described have come to be, and to be empathetic to these circumstances from multiple perspectives. They don’t have to wait for a textbook to tell this story—from each other they learn to develop and refine their perspectives. This poem shows how fluid our borders can be when we create and perform poetry and other creative texts. It shows how fluid our borders as academics and rhetoricians could be if we could listen and engage with such knowledges more effectively.

Background images in this section from mural and grafitti photographs by Steev Hise.

Once the poems, publicly available on YouTube, were coded, we organized and advertised a member check, in order to have a conversation with TYPS youth about our findings: our results from qualitative and quantitative analyses, our codes, and our interpretations. We wanted TYPS youth to become involved in the research and feel free to be critical about the preliminary conclusions we were drawing. Seven TYPS youth attended the member check, in addition to Sarah Gonzales and Logan Phillips, the adult allies who started and coordinated TYPS.

Participants in the member check felt that the following codes fit well with their poetry:

Although our intentions were not to be comprehensive in the identification of themes, we asked TYPS youth what themes seemed to be missing from our analysis. They added the following keywords to our discussion:

Participants felt that one theme didn't seem to belong: limited options to health care. Health is one of the foci of the Crossroads Collaborative, and we included this point because of Arizona legislation, particularly regarding sex education, that affects youths’ options for access to and knowledge about comprehensive health and health care. It is quite possible that the wording in our coding process does not address these issues in a way that speaks to youth, an issue we should always be cognizant of as action-oriented researchers and that underscores the purpose of an approach such as member check, in which we wished to involve TYPS youth in clarifying and engaging with the research. The member check also offered an opportunity for the collaborative to develop its desired role as that of a group of action-oriented researchers who are also community teacher-researchers interested in facilitating an understanding along with youth about the meanings and uses of academic or context-specific terms and how these terms might be relevant to their lives. Other examples include those phrases or terms about which TYPS youth expressed confusion or requested clarification, such as “rights vis-à-vis borders,” “access to relevant knowledgesWe deploy the term KNOWLEDGES rather than “knowledge” to be explicit about the different—sometimes competing, sometimes complementary—knowledges that circulate in the communities in which we are engaged. These range from academic knowledges across disciplinary boundaries, to youth knowledges, to broader community knowledges. Recognizing that different knowledge systems are at play in and from distinct locations, we can also recognize that such knowledges are valid and can inform our research. When we position ourselves as learners who can be informed by the lived knowledges guiding everyday decisions, we open ourselves to deeper understandings of youth practices, interests, needs, strengths, dreams, and desires. In the Crossroads Collaborative, we also work to ensure that differing knowledges are translated, so that those of us involved in local collaborations are legible to one another as collaborators who share interests around youth, sexuality, health, and rights.,” and “heteronormativity.” In the case of “rights vis-à-vis borders, for instance, Crossroads researchers present at the member check described the expansiveness of the term “borders,” as “borders” could refer to the physical borders between Mexico and the United States, a subject of great interest to many of the TYPS poets, or to the nebulous borders between identifications and abstractions, such as sexuality.

At the member check, TYPS poets expressed interest in the ways in which others were viewing their poetry:

I think it’s really interesting because, you know, um, it kind of gives you an idea of how people would label your-your work, in sometimes different and sometimes the same sense, like, as when you were writing it.

You might think about it one way, cause you’re like, you wrote it, and in your mind you’re like, Oh, it’s about this or have it labeled out and then someone comes up to you, Oh, that was really great, that line about—blehhh, whatever it was—and that wasn’t, like, what you were thinking about when you wrote it, and then you kind of look at it again, and you’re like, Huh, that’s true.

Such commentary led to reflections about who they are as poets, how they define their poetry, and how others see their poetry. Of significant note here is that TYPS youth were talking about their individual bodies of work as poets, thus claiming the identities of poet, writer, performer. TYPS poets also expressed a familiarity with each other’s work and emphasized the individual nature of these poems:

[...] when you read them, like, specific poems come to mind, like, that’s so Enrique’s poem, or that’s so Zack’s poem [...]

Sarah and Logan, the directors of TYPS, clarified how and when certain themes may have come up. For instance, Sarah pointed out that poems may have emerged through the exercises from YWCA’s Nuestra Voz racial justice program, which some of the TYPS poets had attended. While youth poets agreed, they were also quick to point out how they feel that they are developing their own voices, styles, and subjects beyond the initial pedagogical exercises introduced by Sarah, Logan, and guest poets with whom they workshop. They said that their personal concerns are political, and, when prodded about what they meant by “political,” one poet said:

Issues that are going on that hit the poet pretty hard, like, recently, like you know some poems are about sexuality because some people like during school, there’s bullying. [...] issues that are here in Arizona such as some stuff with abortion and along with SB 1070 and [...] ethnic studies thing, um, stuff like that, um, that we find unfair that hits us home, so it feels, it’s like one of those things that we can really truly strongly write about, and have a good outcome with it because of really strong emotions.

Another poet discussed her use of the political as a way to get around not wanting to reveal too much about herself in performance:

I’m really bad at putting my personal life out there, so I kind of cover it with, with what’s been going on around here, [...] and school is pretty much our connection to the government or political stuff.

In the dialogue with youth, Logan pushed us as researchers to think more critically about the way we were approaching the poems as data.

[...] coming to this kind of analysis of poetry from being a poet myself, from thinking about poetry for a lot of years, um, I find myself very resistant to this whole idea, um, because, you know, so what if there’s two lines about health care in my poem. You know, that may or may not have any relevance to the rest of the theme of my poem, to me or not, you know, and from an outside perspective—OK, so I mentioned health care twice, but does that have anything really to do with what the nuance of the poem is about. Maybe it does and maybe it doesn’t, and that’s a really hard thing to put a “2” next to. How much is this mentioned related to the-the overall theme of what the poem-the poem seems to be expressing. And it’s also a very hard thing to put objective numbers on very subjective experiences, as we all know from slam, when you get a 5. [...] it’s all 10s, it should be all 10s, but it’s—but that’s the game, is, like, you know, it’s-it’s, these are the numbers for you all. These aren’t the numbers, maybe, for me, or for somebody else—right, maybe I would have never heard, um, “addressing historical trauma” in a poem if I came from a place where that trauma was still continuing and I wouldn’t consider that historical, right, something like that. [...] I think it’s interesting to look at now [...] it’s like when you’re editing a poem, you turn on the critical mind, and you’re going back and revising it—that’s the mind that’s interesting to look at this, but, like, as a poet, I’m very resistant and have always been to sitting down and being like, “OK, I’m gonna write a poem about ‘holders/producers of knowledge.’ Here we go.” Because I’ll never write anything.

Our approach is about each specific poem and how it illuminated or otherwise instantiates the issues that define the Crossroads Collaborative. We find our task to be about really listening to the poetry and hearing it for what is being said and uncovered, discovered, and produced. And our roles as researchers are one reason we wanted to present the findings to the TYPS group. Sarah urged the group to consider the role of research and researchers:

it’s important to [...] think about what this means because, like, if researchers wanted to say, [...] “Oh, we talked to a bunch of youth poets, and, you know, they’re all really sad, or they only are interested in their own identity development.” That would be, like, that would be detrimental, right, and so that’s why—that’s all we do [laughter]—and that, that gives politicians and all these other folks, teachers, any adults, really, the power and capacity to say, “Well, we don’t need to involve youth voice in this because all they’re interested in is themselves.”

In response to Sarah and Logan, we spoke about the ways we wanted to put numbers and stories into conversation. Logan responded:

I think that the experiment is super valid. I mean, that’s why I was really excited about this whole idea cause it’s like a different way to look at our poems, you know. Can it be done? I don’t know, but it’s an interesting thing. It’s like, you know, scoring a poem really is pointless, but it provides kind of an interesting dynamic. The thing itself is really valid, like—I wouldn’t, like I’m not saying this is or isn’t valid, but it’s, that’s kind of beside the point, it’s like what positivity, or what can we learn from this, just like we can learn from a score, but, it doesn’t, it’s not the end-all, be-all of experience, and that’s why I think it’s interesting.

Through the member check we were reminded of the significance of transparency and participation in our work. The practice of being in conversation with youth poets as research participants gives us direction for future research projects and related conversations about thematic interpretations. These findings are in keeping with the purpose of action-oriented participatory research with youth: namely, to incorporate youth visions and voices, not simply as a way of showing what they are capable of, but rather as a way of involving them in the decision-making processes of their local contexts and, in this case, in the scholarly interpretations and analytic insights that are produced in the research process. The dialogues shared here revealed how our perspectives on data did and did not resonate with TYPS youth, demonstrated the ways in which TYPS youth understand and express themselves as writers, and clarified the significance of research with and about youth.

Background images in this section from mural and grafitti photographs by Steev Hise.