[ Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1928) with illustrations by Hume Henderson ]

II. The Pool of Tears

And she began thinking over all the children she knew that were of the same age as herself, to see if she could have been changed for any of them. "I'm sure I'm not Ada," she said, "for her hair goes in such long ringlets, and mine doesn't go in ringlets at all; and I'm sure I can't be Mabel, for I know all sorts of things, and she, oh! she knows such a very little! Besides, she's she, and I'm I, and—oh dear, how puzzling it all is!"

What's in a name? Lewis Carroll should certainly know—he revised the title of Alice's stories to emphasize "Wonderland" for its first printing, and likewise rewrote his own identity. But while Charles Dodgson took on a new name to publish the Alice stories, Alice herself kept her tie to the "original" Alice—at least in some versions. But the centrality of Alice's name to her identity has led to debates about naming when translating Alice, as Christiane Nord notes.

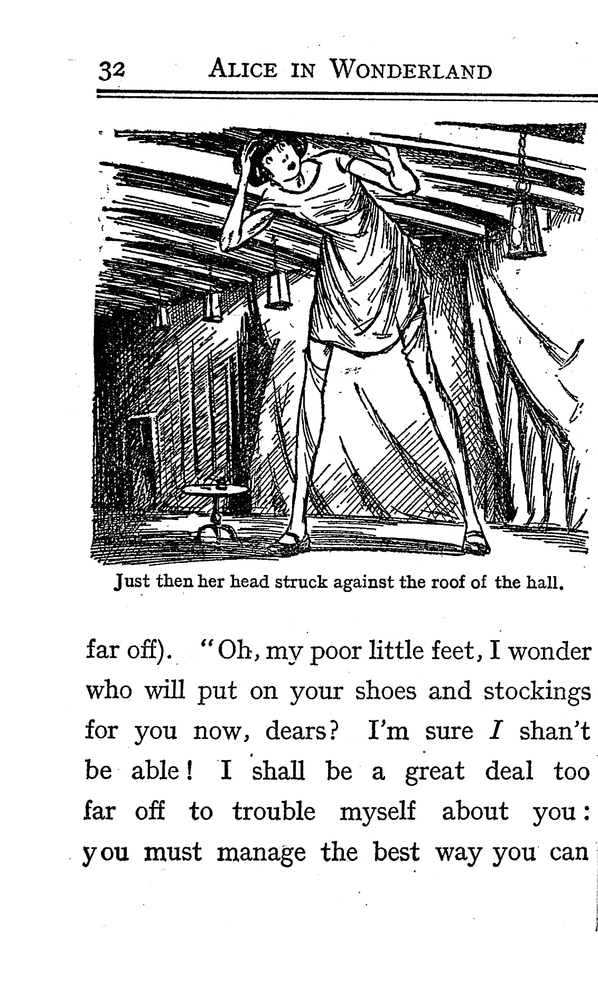

Alice searches for answers to her own identity apart from her physical body in stories and memorized facts, though none of them come out the way she expects. Jerome Bruner notes that narrative is essential to the creation of identity: "it is through narrative that we create and re-create selfhood" (85). The Alice drawn by Hume Henderson has already leapt out of Victorian style, though her shoes still carry a familiar silhouette. The dialogue between written and illustrated narrative creates Alice's self, in an act of adaptation akin to that faced by translators.

The existing University of Florida Afterlife of Alice & Her Adventures in Wonderland digital collection of Alice in Wonderland versions and adaptations offers a digitized prelude to the reincarnations of Alice currently around the web. As we swim out of the pool of printed, illustrated editions, the narrative will continue to guide us through the re-creation of Alice's self even as we use Alice to probe at the nature of narrative. This, then, brings us to the next stage of Alice's "afterlife," and offers a provocation to revisit Alice's own question: if Alice is not the same as she was yesterday, who is she now? How does continual remediation and adaptation alter the original, and how must new media studies and digital humanities methods cooperate for an understanding of the text that considers this complete and mutating identity?